Organ Transplant Recipients: Immunosuppressant Drug Interactions and Side Effects

What Immunosuppressants Do After an Organ Transplant

Your new organ is a gift, but your body doesn’t know that. To your immune system, it’s an invader. That’s why you need immunosuppressant drugs - to quietly turn down your body’s natural defense system so it doesn’t attack the transplant. Without these drugs, rejection happens fast. In the early days of transplants, most patients lost their new organs within weeks. Today, thanks to immunosuppressants, over 90% of kidney transplants still work after one year. But these drugs aren’t magic pills. They come with a long list of side effects, dangerous interactions, and lifelong risks.

The Three Pillars of Transplant Medication

Most transplant patients take a mix of three drugs, sometimes more. This is called triple therapy. The most common combo includes:

- Calcineurin inhibitors - tacrolimus (Prograf) or cyclosporine (Neoral). These are the backbone. About 92% of U.S. kidney transplant recipients take tacrolimus because it works better than cyclosporine at preventing rejection.

- Antimetabolites - mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept) or azathioprine (Imuran). These stop immune cells from multiplying.

- Corticosteroids - usually prednisone. These reduce inflammation but cause some of the most visible side effects.

Some patients get mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus instead, especially if their kidneys are getting damaged by calcineurin drugs. These are less toxic to kidneys but can cause mouth sores and high cholesterol.

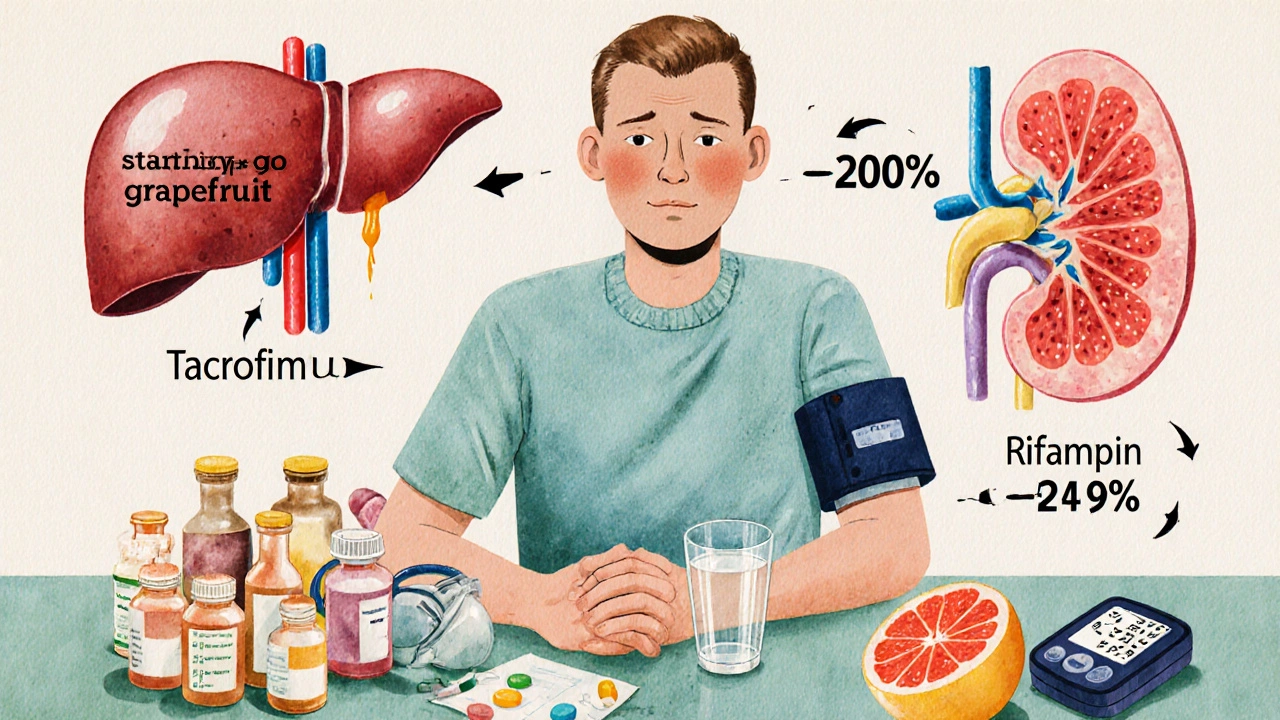

How These Drugs Interact With Everything Else You Take

Immunosuppressants don’t live in a vacuum. They’re processed by the same liver enzymes as hundreds of other drugs. A simple change - like starting an antibiotic or stopping an antacid - can send your drug levels soaring or crashing.

Tacrolimus is especially tricky. It’s broken down by CYP3A4, a liver enzyme. If you take something that blocks that enzyme - like fluconazole (a fungal infection pill), grapefruit juice, or even some heartburn meds - your tacrolimus levels can jump by 50% to 200%. That means kidney damage, tremors, or even seizures. On the flip side, rifampin (used for tuberculosis) or St. John’s wort can drop your levels by 60-90%. That’s a fast track to organ rejection.

Even over-the-counter stuff matters. Ibuprofen and naproxen can hurt your kidneys when combined with tacrolimus. Antacids like omeprazole can change how well your body absorbs the drug. That’s why every transplant center gives you a list of meds to avoid - and why you need to tell every doctor, dentist, or pharmacist you see that you’re on transplant drugs.

The Most Common Side Effects - And What They Really Mean

Side effects aren’t just annoyances. They’re warning signs. Here’s what most patients actually deal with:

- High blood pressure - affects 78% of recipients. Often from steroids and calcineurin drugs. Left unchecked, it damages your new organ.

- New-onset diabetes - happens in 20-30% of people on tacrolimus. Your body stops making enough insulin. You’ll need to check your blood sugar daily.

- High cholesterol - 62% of patients have it. Statins help, but some cholesterol meds can interfere with your immunosuppressants. Your transplant team picks ones that are safe.

- Weight gain - especially from steroids. Many gain 15-20 pounds in the first six months. It’s not just fat - it’s fluid and muscle changes.

- Moon face, buffalo hump - those are steroid side effects. Patients say they feel like they don’t recognize themselves in the mirror.

- Diarrhea, nausea, stomach pain - mycophenolate causes this in up to 50% of people. Some switch to azathioprine, but that brings its own risks like low white blood cell counts.

- Shaking hands, tremors - common with tacrolimus. Some patients can’t hold a coffee cup or write clearly.

- Chronic fatigue - reported by 72%. Not just tiredness. A deep, unrelenting exhaustion that doesn’t go away with sleep.

One Reddit user, u/KidneyWarrior, wrote: “I’m tired all the time. My hands shake. I gain weight. But if I skip a pill, I could lose my kidney. It’s a constant trade-off.”

Long-Term Risks: Cancer and Infections

Your immune system isn’t just fighting off rejection - it’s also hunting down cancer cells and viruses. When you suppress it, you open the door.

Transplant patients are 2-4 times more likely to get skin cancer. Nonmelanoma skin cancers affect 23% of liver transplant recipients. Melanoma risk is also higher. That’s why you need a full-body skin check every 6 months.

Other cancers spike too - especially lymphoma, lung cancer, and HPV-related cancers (like throat and cervical). HPV-related cancers occur 100 times more often than in the general population.

Infections are just as dangerous. Pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and even common colds can turn deadly. You’re told to avoid raw fish, undercooked meat, and unpasteurized cheese. You wear masks in crowded places. You report a fever of 100.4°F or higher immediately - no waiting.

One study found that 68% of adverse events linked to immunosuppressants are infections. Another 15% are cancers. These aren’t rare. They’re expected.

How Doctors Monitor You - And What You Need to Do

You’re not left alone with this. Your transplant team runs constant checks:

- Drug levels - tacrolimus blood tests start twice a week, then weekly, then monthly. Too high? You risk kidney damage. Too low? Rejection looms.

- Blood counts - every month. To catch low white cells, anemia, or low platelets.

- Lipid panels - every 3 months. Cholesterol and triglycerides are closely watched.

- Glucose tests - every 6 months. To catch diabetes early.

- Kidney function - creatinine and GFR checked regularly. A drop in GFR means your drugs might be harming your new organ.

Most centers require you to live within 2 hours of the hospital for the first year. Why? Because if you get sick, you need to be seen fast. No delays.

Medication adherence is critical. About 25-30% of patients struggle with the pill burden - often 8 to 12 pills a day, at specific times. One Cleveland Clinic study found that using electronic pill dispensers boosted adherence from 72% to 89%. That’s the difference between keeping your organ and losing it.

What’s Changing - And What’s Coming

There’s progress. In 2023, the FDA approved voclosporin, a new calcineurin inhibitor with fewer kidney side effects than tacrolimus. Early data shows 24% less kidney damage.

Belatacept (Nulojix), a drug that works differently, is showing promise. In a 7-year study, it cut cardiovascular deaths by 30% and cancer rates by 25%. But it has a catch: higher early rejection rates. So it’s only used in select patients.

More centers are dropping steroids early - within 7 to 14 days after transplant - if the patient is low risk. This reduces moon face, weight gain, and bone loss.

The big hope? Immune tolerance. Researchers are testing ways to teach the body to accept the new organ without drugs. One study found that 15% of kidney transplant patients could stop all immunosuppressants after T-cell therapy. That’s not common yet - but it’s real.

Living With the Balance

There’s no perfect solution. Every drug has a cost. Every side effect changes your life. But without these drugs, you wouldn’t be alive with a new organ.

The goal isn’t to avoid side effects. It’s to manage them. To know what’s normal and what’s dangerous. To speak up when your hands shake too much, when your skin looks odd, when you’re too tired to get out of bed.

One patient, u/LiverSurvivor, switched from tacrolimus to sirolimus after his kidney function dropped. His GFR improved from 38 to 52. But he got mouth ulcers and high cholesterol. “It’s not better,” he said. “It’s different.”

That’s the reality. You’re not cured. You’re maintained. And that maintenance requires constant attention, communication, and courage. The transplant isn’t the end of your medical journey - it’s the start of a new one. One where you learn to live with the quiet, necessary trade-off: a functioning organ, and a body that’s been changed forever.

15 Comments

Jennifer Shannon

November 21, 2025 at 18:47

Wow. This post is like a masterclass in how medicine balances life and loss. I’ve watched my cousin go through a liver transplant, and honestly? The real story isn’t in the drugs-it’s in the quiet mornings where she stares at her pills and wonders if the weight gain, the tremors, the exhaustion are worth it. And then she drinks her coffee, checks her blood sugar, and does it again. There’s no heroism here, just stubborn, daily love for being alive.

It’s not just about avoiding grapefruit juice-it’s about living in a world where your body is both a temple and a battleground. And nobody tells you how lonely that feels when your friends move on to their next vacation or new job, and you’re still counting pills at 3 a.m.

Suzan Wanjiru

November 22, 2025 at 13:43

Key point missed here-tacrolimus levels are monitored by trough levels not random draws. Always draw before the next dose. Also, mycophenolate GI side effects can be mitigated with enteric-coated versions. Many centers switch to EC-MPS early. And yes, steroids are being dropped faster now-especially in low-risk recipients. Don’t forget to check for CYP3A5 genotype. Fast metabolizers need higher doses.

Lisa Lee

November 24, 2025 at 05:28

Why are we even doing this? Canada has universal healthcare but still lets people take 12 pills a day just to stay alive? This is just corporate medicine exploiting desperate people. If your body rejects a transplant, maybe it’s supposed to.

Henrik Stacke

November 25, 2025 at 21:57

What strikes me most is not the pharmacology-but the psychological toll. The constant vigilance. The fear of a fever. The way your identity shrinks to a blood test result. I’ve spoken with transplant recipients in London, and they all say the same thing: "I’m not cured. I’m maintained." And that’s a haunting phrase, isn’t it? It doesn’t sound like hope. It sounds like survival with a price tag.

Manjistha Roy

November 27, 2025 at 00:33

Thank you for sharing this detailed breakdown. Many people don't realize how much coordination is required between specialists. Every new medication-even herbal supplements-must be cleared by the transplant team. This is not something you can manage alone. It requires a team, a system, and a patient who is willing to be their own advocate. Please, if you are on immunosuppressants, never assume a new doctor knows your regimen. Always carry a card.

Jennifer Skolney

November 28, 2025 at 17:12

My sister got a kidney transplant three years ago. She went from being bedridden to hiking mountains. But she also got diabetes, high blood pressure, and can't eat sushi anymore. She says it's worth it-but I see the toll. The way she flinches when the pharmacy calls about her drug levels. The way she cries when she sees her reflection. I just wish there was a way to fix this without making people pay with their bodies. 💔

JD Mette

November 29, 2025 at 22:02

It’s interesting how the body becomes a site of constant negotiation. You’re not healing-you’re managing. There’s no finish line. Just checkpoints. And the medications? They’re not tools. They’re companions. Unwelcome, necessary, and always watching.

Olanrewaju Jeph

December 1, 2025 at 20:43

Correct usage of pharmacokinetic terms is critical. Tacrolimus is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, with CYP3A5 polymorphisms significantly influencing dosing requirements. In African populations, the *1/*1 genotype is prevalent, leading to higher clearance rates. This necessitates higher initial doses. Failure to account for this leads to subtherapeutic levels and increased rejection risk. Always consider genetic background in dosing protocols.

Dalton Adams

December 3, 2025 at 04:03

Let’s be real-this post is just a glorified drug pamphlet. The real problem? The system. Why are we still using 1980s-era immunosuppressants? Why isn’t gene editing being used to induce tolerance? Why are patients forced to take 12 pills a day when a single CRISPR edit could theoretically reprogram T-cells? The science is here. The bureaucracy isn’t. And until big pharma stops profiting off lifelong dependency, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Also, grapefruit juice? Please. That’s a 1990s warning. Modern LC-MS/MS monitoring makes that obsolete. You’re not a caveman. Test your levels. Don’t rely on fruit myths.

Kane Ren

December 4, 2025 at 10:20

It’s not about the drugs. It’s about the courage. Every day, someone takes their pills even when they feel like garbage. Even when their hands shake. Even when they hate their reflection. That’s not compliance. That’s heroism. Keep going. You’re not broken. You’re becoming.

Charmaine Barcelon

December 4, 2025 at 12:35

Why do people think this is normal? You’re not supposed to gain 20 pounds, shake all day, and get skin cancer just to stay alive. This isn’t medicine. It’s a compromise. And if you’re okay with that, you’re not brave-you’re resigned.

Karla Morales

December 6, 2025 at 03:36

📊 DATA DUMP: 72% fatigue. 62% dyslipidemia. 20-30% new-onset diabetes. 23% nonmelanoma skin cancer. 68% of adverse events = infections. 25-30% non-adherence. The numbers don’t lie. This isn’t a miracle. It’s a high-stakes gamble with your immune system. And guess who pays? The patient. Not the hospital. Not the pharma exec. YOU. 💀

Javier Rain

December 6, 2025 at 06:38

Look-I’ve been on this ride for 11 years. I’ve had two rejections. I’ve lost friends to infections. I’ve cried over my bloodwork. But I’m still here. And I’m not done. If you’re reading this and you’re scared? Good. That means you care. Now go take your meds. Call your team. Tell someone how you really feel. You’re not alone. We’re all still here. Fighting. One pill at a time.

Laurie Sala

December 7, 2025 at 15:55

I just read this and I’m sobbing. I lost my brother to rejection because he skipped a dose because he was tired. He thought he could handle it. He thought he was fine. And now he’s gone. And I have to live with that. Please. Please. Don’t be like him. Take your pills. Even when you hate them. Even when you hate yourself. Even when you just want to sleep. Take. Them.

Kezia Katherine Lewis

December 9, 2025 at 07:38

Belatacept’s mechanism of action-CD28-B7 costimulation blockade-is revolutionary, but the early rejection rates (up to 15% in year one) are non-trivial. It’s reserved for patients with low immunologic risk and no prior sensitization. Also, IV administration every 4 weeks is a logistical burden. But the long-term renal and cardiovascular benefits? Unmatched. This isn’t a replacement-it’s a strategic pivot for select populations.