Presumed Consent in Pharmacy: When Pharmacists Can Switch Your Medication Without Asking

Every year, over 4 billion prescriptions are filled in the U.S. Most of them - about 90% - are for generic drugs. But here’s the thing: you probably didn’t sign anything to make that switch. In 43 states, pharmacists don’t need your permission to swap your brand-name pill for a cheaper generic version. They just do it. That’s called presumed consent.

What Presumed Consent Actually Means

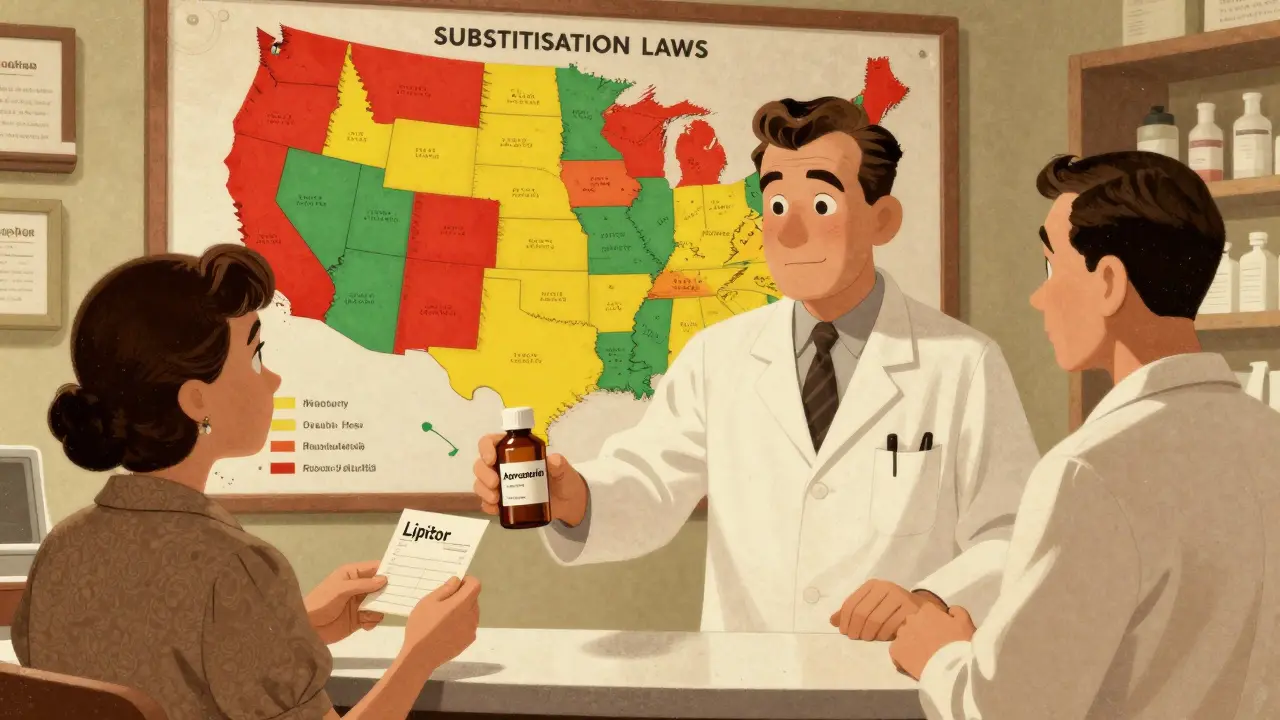

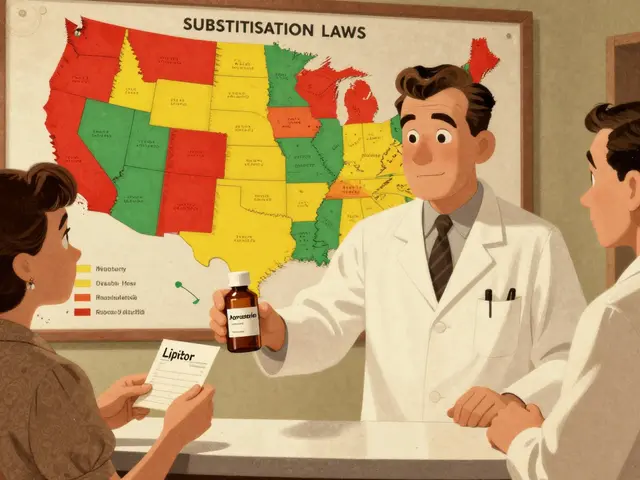

Presumed consent isn’t a loophole. It’s the law in most places. If your doctor prescribes Lipitor, and there’s an FDA-approved generic version of atorvastatin available, the pharmacist can give you the generic without asking. They assume you’re okay with it - because the system is built to save money and time. The FDA says these generics are just as safe and effective. Same active ingredient. Same dosage. Same results. But that doesn’t mean you’re always told. In many states, you won’t hear a word until you get your receipt - and see a different name on the bottle. That’s because presumed consent laws only require notification after the switch, not before. Some states don’t even require that. Others demand a written note or a phone call. It’s messy.How It Works: The State-by-State Patchwork

There are 50 states. Each one has its own rules. That’s the biggest headache for pharmacists - and patients.- In 19 states, pharmacists must substitute generics if available. That’s mandatory substitution. Texas, California, and Illinois are on that list.

- In 31 states, substitution is allowed but not required. The pharmacist can choose.

- In 7 states and Washington, D.C., pharmacists need your explicit permission - no exceptions. That means they have to ask you, face to face, before swapping.

- In 31 states plus D.C., you must be notified after the switch. That notification can be on the label, a printed slip, or a digital message.

The Dangerous Exceptions: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Some medications have a razor-thin margin between working and causing harm. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. A tiny change in blood levels - even from a generic that’s technically “equivalent” - can mean the difference between control and crisis. Antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin, warfarin (blood thinner), lithium (for bipolar disorder), and certain thyroid meds fall into this category. The American Epilepsy Society tracked 178 cases of breakthrough seizures between 2018 and 2022 linked to generic switches. That’s not theoretical. That’s real people. Fifteen states now have special rules for NTI drugs. In Hawaii, Tennessee, and New York, pharmacists can’t swap these without your explicit consent. In others, they can - but they’re supposed to flag it in the system. The problem? Electronic prescribing systems often don’t catch it. A 2023 ASHP survey found that 41% of pharmacists in presumed consent states struggled with tech that didn’t block substitutions for these high-risk drugs.

What About Biosimilars? It’s Even More Complicated

Biosimilars are the next wave of generics - but for complex biologic drugs like Humira, Enbrel, or insulin. These aren’t simple chemical copies. They’re made from living cells. That means even small changes in manufacturing can affect how they work. Only 6 states let pharmacists automatically swap interchangeable biosimilars without telling you. Four states - North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Texas - ban automatic substitution entirely. The rest? A gray zone. Some require the prescriber to write “dispense as written.” Others allow substitution but demand extra documentation. The FDA’s Purple Book lists which biosimilars are interchangeable. But pharmacists don’t always know how to use it. A 2023 survey found that only 35% of independent pharmacies had updated their training on biosimilar substitution rules.Why This System Exists: The $1.68 Trillion Reason

The reason presumed consent laws exist isn’t to trick you. It’s to save money. And it works. Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions but only 15% of total drug spending. Over the last decade, they’ve saved the U.S. healthcare system $1.68 trillion. That’s not a guess. That’s from the Association for Accessible Medicines. Pharmacists save about 1.7 minutes per prescription by not having to ask for consent. Multiply that by 4 billion prescriptions - that’s over $2.8 billion in labor savings a year. Insurance companies love it. Medicare Part D beneficiaries save an average of $627 per year because of these switches. But here’s the trade-off: efficiency comes at the cost of control. You’re not being asked. You’re being assumed.What Patients Really Think

Most people don’t notice. A Drugs.com survey of 1,243 patients found 68% were happy with the switch - “saved me $45 a month” was the most common comment. But 22% weren’t. One patient wrote: “My seizure meds stopped working after they switched me to generic. I ended up in the ER.” That’s not rare. The Epilepsy Foundation logged 312 substitution-related adverse events in 2022. Sixty-seven percent happened in states without special NTI protections. On Reddit, a pharmacist in Ohio shared: “95% of patients don’t care. The other 5%? They never trust us again.” That’s the real tension: saving money versus building trust. If you feel like your care is being treated like a commodity, you’re not wrong.

What You Can Do: Know Your Rights

You don’t have to accept this passively.- Ask your doctor to write “dispense as written” or “no substitution” on your prescription. It’s legal. Pharmacists must follow it.

- Check your bottle every time. If the name or color changed, ask why.

- Call your pharmacy and ask what their substitution policy is. Most will tell you - if you ask.

- Know your state’s rules. Search “[your state] pharmacy substitution law 2026” - you’ll find your state board’s website with the exact details.

- If you’re on a high-risk drug (epilepsy, blood thinners, thyroid, etc.), insist on the brand. If they say no, ask to speak to the pharmacist-in-charge.

The Future: Will This Change?

The pressure is building. The American Medical Association wants stricter rules for NTI drugs. The Uniform Law Commission is pushing a Model State Substitution Act to standardize rules across states. Right now, you need to memorize 51 different sets of rules. That’s absurd. A 2022 report from the National Academy for State Health Policy suggested a “tiered consent” model: presumed consent for most drugs, but explicit consent only for high-risk ones. That’s the smart middle ground. Meanwhile, biosimilars are coming fast. By 2028, they could make up 25% of the biologics market. If we don’t fix the rules now, we’ll see more confusion - and more avoidable harm.Bottom Line

Presumed consent isn’t evil. It’s practical. It saves billions and keeps medications affordable. But it’s not perfect. It assumes you’re okay with change - even when you might not be. If you’re on a routine medication for high blood pressure or cholesterol? Go ahead. The generic is fine. If you’re on a drug where even a small change could hurt you? Don’t assume. Ask. Push back. Write it on the script. Make sure your pharmacist knows. Your health isn’t a cost-saving metric. It’s your life. And you deserve to be part of the decision - even if the law says you don’t have to be.Can a pharmacist legally switch my brand-name drug without asking me?

Yes, in 43 states and Washington, D.C., pharmacists can substitute a generic version of your prescription without asking for your permission. This is called presumed consent. They’re required to notify you after the switch in most cases, but not before. Only 7 states and D.C. require explicit consent before substitution.

Are generic drugs really as good as brand-name ones?

For most medications, yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They must also meet the same strict manufacturing standards. Over 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics because they’re proven safe and effective. But for certain drugs - like antiseizure meds, blood thinners, and thyroid pills - small differences in how the body absorbs the drug can matter. These are called narrow therapeutic index drugs.

What should I do if I think my generic medication isn’t working?

Don’t stop taking it. Call your pharmacist right away and ask if your medication was switched. If it was, ask if you can go back to the brand or try a different generic. Then contact your doctor. Keep a record of when you started the new pill and what symptoms you noticed. If you’re on a high-risk drug like warfarin or phenytoin, insist on getting the same version every time - even if it costs more. Your safety matters more than the price tag.

Can I stop a substitution before it happens?

Yes. Ask your doctor to write “dispense as written” or “no substitution” on your prescription. That legally blocks the pharmacist from switching it. You can also tell the pharmacist when you drop off the script: “I don’t want this switched.” They must honor it, even in presumed consent states. Some pharmacies will still try to convince you - but you have the right to say no.

Why do some states require consent and others don’t?

It’s a mix of politics, economics, and patient advocacy. States with stronger pharmacy associations and more generic drug manufacturers tend to favor presumed consent because it reduces costs and speeds up service. States with strong patient advocacy groups - especially those representing people with epilepsy or chronic conditions - pushed for explicit consent laws. There’s no national standard, so each state made its own choice based on local priorities.

Do I have to pay more if I want the brand-name drug?

Sometimes. If you choose the brand-name drug after a generic is available, your insurance may not cover it fully - or at all. You might have to pay the full cash price. But if your doctor writes “dispense as written,” your insurance usually still covers it. Some pharmacies offer discount programs for brand-name drugs if you can’t afford the generic. Ask your pharmacist - they might know of one.

8 Comments

Austin Mac-Anabraba

January 1, 2026 at 15:23

Presumed consent isn't a violation of autonomy-it's the logical extension of a market-driven system optimized for efficiency. You don't ask your grocer if you want store-brand cereal instead of Kellogg's. You don't demand branded toilet paper because you 'feel better' with it. The FDA's bioequivalence standards are rigorous. If you're not on an NTI drug, your resistance is performative, not principled. The real issue? The system doesn't educate patients-it just automates savings. That's not malice. It's negligence dressed as economics.

Phoebe McKenzie

January 2, 2026 at 04:48

THIS IS WHY AMERICA IS FALLING APART. They switch my blood thinner without telling me and then act like it's no big deal? I had a stroke last year because of this exact thing-my INR went haywire after they swapped my warfarin for some cheap generic. The pharmacist didn’t even look me in the eye. This isn’t saving money-it’s medical negligence with a corporate stamp on it. Someone needs to go to jail for this. I’m calling my senator tomorrow.

gerard najera

January 3, 2026 at 16:08

Autonomy matters. Efficiency matters. But when they conflict, you don’t sacrifice one for the other-you redesign the system.

Stephen Gikuma

January 3, 2026 at 22:06

They’re not just swapping pills. They’re testing you. This is part of the Great Pharma Reset. The government, Big Pharma, and the FDA are all in cahoots. They want you dependent on generics so they can control your biochemistry silently. Watch what happens when biosimilars hit insulin-next thing you know, your blood sugar’s being fine-tuned by algorithm. Wake up. This isn’t healthcare. It’s bio-surveillance with a pharmacy counter.

Bryan Anderson

January 5, 2026 at 16:12

I appreciate the depth of this breakdown. As a pharmacy technician, I can confirm that the state-by-state patchwork creates real operational chaos. We’re trained to check the Orange Book, verify NTI flags, and honor 'dispense as written'-but many EHR systems don’t flag NTI drugs properly. I’ve had to manually override substitutions three times this month for patients on phenytoin. The system is designed to save money, but it’s failing patients who need consistency. We need mandatory electronic alerts for high-risk drugs across all states. It’s not just ethical-it’s technically feasible.

Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 6, 2026 at 18:05

Coming from India, where generics are the norm and patients rarely question them, I find this debate fascinating. Here, cost is the primary driver-and trust is built through relationships, not laws. My grandmother takes her generic antihypertensive without hesitation because her pharmacist knows her by name. Maybe the answer isn’t more regulation, but more human connection. If pharmacists took 30 seconds to say, 'I switched your pill today-let me know if you feel different,' would people still feel violated? Maybe the issue isn’t the law-it’s the silence.

Liam George

January 6, 2026 at 22:40

Let’s be clear: presumed consent is the first domino in a pharmacological control architecture. The FDA’s Orange Book isn’t science-it’s a regulatory fiction. Bioequivalence studies are conducted on healthy volunteers, not elderly patients on polypharmacy regimens. The 90% generic adoption rate? That’s not patient preference-it’s insurance coercion. And now they’re pushing biosimilars with the same playbook. The Purple Book? A placebo for transparency. The real agenda? Consolidate drug manufacturing under fewer corporate entities, eliminate brand loyalty, and turn every patient into a data point in a centralized pharmacovigilance grid. This isn’t about savings. It’s about total pharmacological compliance. And they’re doing it one pill swap at a time.

sharad vyas

January 8, 2026 at 07:04

Simple truth: if you feel different after a switch, speak up. No one knows your body like you do. Pharmacist is not enemy. But you are the expert of your own health. Ask. Check. Repeat. No shame in that.