Regulatory Exclusivity: How Non-Patent Protections Control Drug Market Access

When a new drug hits the market, it doesn’t just rely on patents to keep competitors away. In fact, many drugs enjoy years of exclusive sales regulatory exclusivity-a government-backed shield that blocks generics and biosimilars from even applying for approval, regardless of whether patents exist. This isn’t a loophole. It’s a deliberate part of U.S. drug law, built into the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 and expanded by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009. While patents protect specific chemical structures or methods, regulatory exclusivity protects the drug itself. And it’s often the real reason why a brand-name drug stays alone on the shelf for a decade or more.

What Regulatory Exclusivity Actually Does

Regulatory exclusivity is not something a company files for. It’s automatic. Once the FDA approves a new drug, and if it meets certain criteria, the agency is legally required to delay approval of any competing version for a set period. During that time, generic manufacturers can’t even submit their applications. That’s different from patents, which require active enforcement through lawsuits. With exclusivity, the FDA itself blocks competitors. No court battles. No legal gray areas. Just a hard stop on approval.

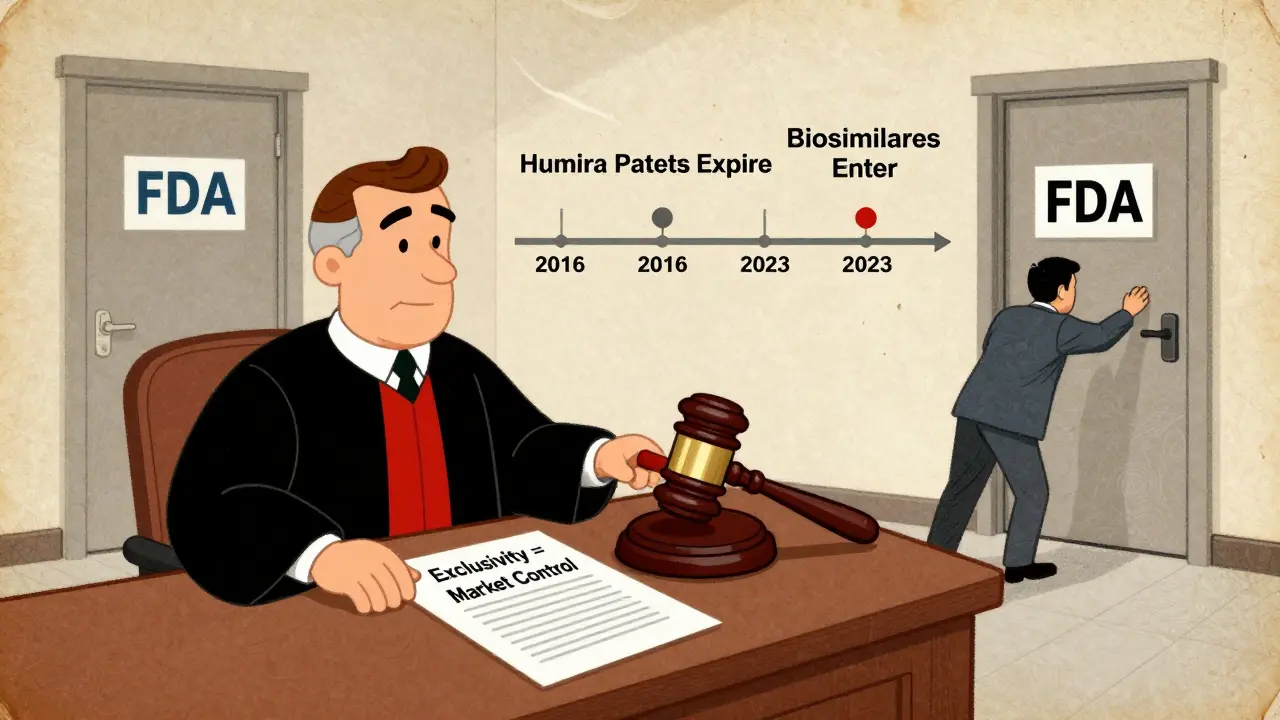

Think of it like a timer that starts ticking the moment the FDA gives the green light. Even if the patent on the drug expires five years earlier, the exclusivity clock keeps running. That’s why drugs like Humira stayed without competition until 2023-even though its key patents expired in 2016. The 12-year biologics exclusivity period was the real barrier.

The Four Main Types of Exclusivity in the U.S.

Not all exclusivity is the same. The FDA grants different types based on the kind of drug and the data behind it. Here’s what you’ll actually see in practice:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years - This applies to drugs with a completely new active ingredient. The FDA won’t accept any generic application for four years, and won’t approve one until the full five years are up. This is the most common type for traditional small-molecule drugs.

- Biologics Exclusivity: 12 years - For complex proteins and cell-based therapies, the law gives 12 years of protection. This was created to account for the longer, more expensive development process. A biologic like Enbrel or Keytruda gets this full term, regardless of patent status.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years - If a drug treats a rare disease affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans, the sponsor gets seven years of exclusivity. This was designed to encourage development for conditions no one else wanted to touch. In 2023, nearly half of all new drug approvals were for orphan indications.

- 3-Year Exclusivity - This kicks in when a company submits new clinical data to support a change in dosage, indication, or delivery method for an already-approved drug. It doesn’t block generics of the original version, but it does stop competitors from copying the new use.

These periods can overlap. A drug might have a patent, NCE exclusivity, and orphan status all at once. The longest one wins. That’s why some drugs have 12 years of protection even when their patents are long gone.

How It Works in Other Countries

The U.S. isn’t the only player. Other major markets have their own rules, and they’re not always aligned:

- European Union - Uses an "8+2+1" system: 8 years of data protection (no generics can use the originator’s clinical data), 2 years of market exclusivity (no sales allowed), and a possible 1-year extension for new indications.

- Japan - Grants 10 years of data exclusivity for new chemical entities, with no separate market exclusivity period.

- Canada and Australia - Both offer 8 years of data protection, but only 2 years of market exclusivity.

These differences matter. A company launching a drug globally has to track multiple clocks. A drug that gets 12 years in the U.S. might only get 8 in Europe. That affects pricing strategy, manufacturing scale, and when to enter each market.

Why Exclusivity Matters More Than Patents for Many Drugs

Patents are great-but they’re fragile. They can be challenged, invalidated, or narrowed in court. Regulatory exclusivity? It’s not touchable. The FDA doesn’t care if a patent is weak. If the drug qualifies, the clock runs. That’s why pharmaceutical companies prioritize exclusivity over patents in their planning.

Take biologics, for example. These drugs often take 10 to 15 years to develop. By the time they’re approved, most of the 20-year patent term is already gone. Without the 12-year exclusivity, companies wouldn’t have enough time to recoup their investment. That’s why the biologics exclusivity term was created-it’s not a bonus. It’s a necessity.

Even for small-molecule drugs, the approval process can take 5 to 7 years. A patent filed at the start of development might expire before the drug even hits shelves. Regulatory exclusivity fills that gap. According to FDA data, the average innovator drug enjoys 12.3 years of combined patent and exclusivity protection. For biologics, it’s 14.7 years.

The Controversy: Too Much Protection?

There’s no debate that exclusivity drives innovation. But it also keeps prices high. A drug with exclusivity can charge 3.2 times more than its generic equivalent, according to IQVIA. That’s why critics say the system is broken.

Public Citizen and other consumer groups argue that 12 years for biologics is excessive. They point out that development costs have dropped with new technologies, and that the original intent-to incentivize risky research-no longer justifies such long monopolies. In 2023, Congress proposed lowering biologics exclusivity to 10 years. It didn’t pass, but the pressure is growing.

On the flip side, originator companies say the system works. A 2024 survey by the Association for Accessible Medicines found that 89% of brand-name companies view exclusivity as essential for recouping R&D costs. Generic manufacturers? Only 42% are satisfied, mainly because they can’t plan ahead. The 4-year waiting period for NCEs forces them to invest in development without knowing if the FDA will ever approve their version.

How Companies Use Exclusivity Strategically

Smart pharma companies don’t just wait for exclusivity-they engineer it.

Some extend exclusivity by filing for orphan status on a new indication. For example, a cancer drug originally approved for breast cancer might get a second approval for a rare subtype, triggering a new 7-year orphan exclusivity period-even if the original patent has expired.

Others time their clinical trials to maximize overlap. If a company knows a patent will expire in 2027, they might delay filing for approval until 2025 so that exclusivity runs from 2025 to 2030, pushing generic entry further out.

And then there’s Humira. AbbVie didn’t just rely on one patent. They filed over 250 patents and layered on exclusivity to delay biosimilars for nearly a decade after the main patent expired. In 2022, Humira made $19.9 billion in U.S. sales alone. That’s the power of stacking protections.

What Happens When Exclusivity Ends?

When the clock runs out, the FDA immediately opens the door. Generic manufacturers who’ve been waiting in the wings can submit their applications. But it’s not instant chaos. The first generic to file often gets 180 days of exclusivity of its own-a reward for taking the legal risk.

That’s why you’ll often see one or two generic versions appear first, then others follow. Prices drop quickly after that. In the first year after exclusivity ends, brand-name sales typically fall by 60% to 80%. In some cases, the drug’s price drops by 90%.

But exclusivity doesn’t always end cleanly. Sometimes, the FDA gets behind on reviews. Other times, legal disputes over patent listings delay generic entry. That’s why tracking exclusivity expiration dates is a full-time job for regulatory teams. Companies hire specialists just to manage these timelines.

What’s Changing in 2025 and Beyond

Regulatory exclusivity is under pressure. The FDA’s 2024-2026 Drug Competition Action Plan says it wants to "modernize" exclusivity rules to better balance innovation and access. The European Union is proposing to shorten data exclusivity from 8 to 6 years. In the U.S., lawmakers are still debating whether 12 years for biologics is too long.

At the same time, new therapies are emerging-like gene therapies and cell therapies-that don’t fit neatly into existing categories. Some experts argue that for these therapies, exclusivity might be irrelevant because they’re too complex to copy. A cell therapy made from a patient’s own cells can’t be replicated like a pill. That could force regulators to rethink the whole system.

One thing’s clear: regulatory exclusivity isn’t going away. But its shape is changing. By 2030, experts predict the average combined protection period for new drugs will drop from 12.3 years to 10.8 years. That’s still a long time-but it’s less than before.

Why This Matters to Patients and Providers

If you’re a patient, exclusivity means you might pay hundreds or thousands more for a drug than you would if generics were available. If you’re a provider, it affects what you can prescribe and when. If you’re a pharmacist, it determines what’s on the shelf.

And if you’re someone who works in healthcare policy, finance, or law, understanding exclusivity isn’t optional. It’s the hidden engine behind drug pricing, access, and innovation. You don’t need to be a lawyer to get it. You just need to know: patents protect inventions. Exclusivity protects markets.

And right now, exclusivity is winning.

What is the difference between patent protection and regulatory exclusivity?

Patents protect specific inventions-like a chemical structure or manufacturing method-and must be actively enforced by the patent holder through lawsuits. Regulatory exclusivity is granted automatically by the FDA upon drug approval and blocks competitors from even submitting applications for a set period. It doesn’t depend on patents and can last even after a patent expires.

Can a drug have both a patent and regulatory exclusivity?

Yes, and most new drugs do. Patents and exclusivity run side by side. The longer of the two determines how long the drug stays without competition. For example, a biologic might have a patent expiring in 2025 but 12 years of regulatory exclusivity running from 2023 to 2035. In that case, generics can’t enter until 2035.

Why does the FDA grant 12 years of exclusivity for biologics?

Biologics are complex proteins made from living cells, and developing them takes longer and costs more than traditional drugs. The 12-year term was designed to ensure companies can recover their R&D investment before generics enter. Without it, many biologics wouldn’t be developed at all.

How does orphan drug exclusivity work?

If a drug treats a disease affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S., the sponsor gets 7 years of exclusivity, regardless of patent status. This was created to encourage development for rare diseases that otherwise wouldn’t be profitable. Even if another company develops the same drug, they can’t get approval during that 7-year window.

Can generic companies challenge regulatory exclusivity?

No. Unlike patents, regulatory exclusivity can’t be challenged in court. The FDA is legally bound to enforce it. Generic companies can only wait it out or develop a different version that doesn’t rely on the originator’s data. Some try to find loopholes, like developing a new formulation, but they can’t bypass the exclusivity period outright.

11 Comments

Meghan Hammack

January 8, 2026 at 14:44

This is wild-I had no idea the FDA could just block generics like that. No court needed? Just a timer? 😱

So Humira stayed at $70k a year because of a paperwork rule? That’s insane.

Gregory Clayton

January 9, 2026 at 15:09

America built this system so we could lead the world in drug innovation. You want cheap drugs? Go to India. We don’t subsidize foreign companies taking our R&D.

Johanna Baxter

January 9, 2026 at 16:05

They call it protection but it’s just corporate greed dressed up as science

12 years for biologics? My grandma’s arthritis drug cost less than my coffee subscription

they’re laughing all the way to the bank while people choose between insulin and rent

Maggie Noe

January 11, 2026 at 08:47

Think about it-patents are about invention, exclusivity is about control.

It’s not capitalism, it’s feudalism with FDA stamps.

They don’t just own the drug, they own the timeline.

And we let them.

Why? Because we’re trained to believe innovation needs cages.

But what if innovation thrives in open fields?

What if competition didn’t mean ‘copy’ but ‘improve’?

What if we stopped treating medicine like a monopoly sport?

Maybe the real breakthrough isn’t a new molecule…

but a new moral imagination.

🫂

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

January 12, 2026 at 21:10

India gives generics in 3 years. US gives 12? That’s why our healthcare is broken. Pharma CEOs don’t care if you die slowly-they care if their quarterly reports look pretty.

Stop pretending this is about science. It’s about profit.

And we’re the ones paying.

Alicia Hasö

January 13, 2026 at 11:59

For anyone working in healthcare access-this is foundational knowledge.

Exclusivity isn’t a footnote-it’s the engine of pricing, supply chains, and patient outcomes.

When I train new pharmacists, I start here.

Because if you don’t understand how the FDA enforces market pauses, you can’t understand why a $10,000/month drug exists.

And you can’t fight for change unless you see the machinery.

It’s not conspiracy-it’s codified policy.

And policy can be changed.

But only if enough of us understand it.

So thank you for this breakdown.

It’s rare to see clarity on this topic.

Keep educating.

Angela Stanton

January 14, 2026 at 03:21

Let’s be real-NCE exclusivity is the ultimate arbitrage.

Pharma firms game the system by filing minor formulation tweaks to reset the clock.

Orphan drug designation? 50% of 2023 approvals? That’s not rare disease innovation-that’s regulatory arbitrage with a PR halo.

And don’t get me started on the 180-day generic exclusivity loophole-first filers get a monopoly on the monopoly.

It’s a Rube Goldberg machine of rent-seeking.

📊📊📊

And we call this innovation?

Patty Walters

January 15, 2026 at 06:50

Just wanted to say-this post saved my butt at work.

I’m a med rep and had to explain to a doc why his patient couldn’t get the generic yet.

Used your breakdown verbatim.

He said ‘I had no idea’ and actually thanked me.

Thanks for making this complex stuff feel human.

Also… i think u meant ‘biosimilars’ not ‘generics’ for biologics? but i get what u mean 😊

Ian Long

January 16, 2026 at 16:47

Look, I get why companies want protection.

But stacking 5-year + 12-year + 7-year exclusivities like legos? That’s not innovation.

That’s legal jujitsu.

And if we keep letting them do it, we’re not just paying more-we’re losing trust in the whole system.

Maybe we need a new category for ultra-complex therapies.

But for regular drugs? 10 years max. Period.

Let’s not punish patients for corporate creativity.

Jerian Lewis

January 18, 2026 at 01:34

Everyone’s mad at pharma but no one wants to pay more taxes to fund public R&D.

So we get this mess.

It’s not evil-it’s a failure of collective will.

We want cheap drugs.

We want innovation.

We don’t want to fund it.

That’s the real conflict.

Not the FDA.

Ashley Kronenwetter

January 18, 2026 at 07:14

Thank you for this comprehensive and well-structured overview. Regulatory exclusivity remains one of the most under-discussed yet pivotal mechanisms in pharmaceutical policy. The international comparisons-particularly the EU’s 8+2+1 model-are essential for understanding global market dynamics. This should be required reading for students in health economics and public policy.