Torsades de Pointes from QT-Prolonging Medications: How to Recognize and Prevent This Life-Threatening Reaction

Every year, thousands of people take medications that quietly mess with their heart’s rhythm-without them even knowing it. One of the most dangerous outcomes is Torsades de Pointes, a chaotic, twisting heart rhythm that can turn deadly in seconds. It doesn’t come with warning signs like chest pain or dizziness. Often, the first clue is a collapsed patient or a flatline on the monitor. But here’s the truth: this isn’t random. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable.

What Exactly Is Torsades de Pointes?

Torsades de Pointes (TdP) isn’t just any irregular heartbeat. It’s a specific type of ventricular tachycardia that looks like the QRS complexes on an ECG are twisting around the baseline-hence the name, which means "twisting of the points" in French. This rhythm only happens when the heart’s electrical recovery phase is too long-when the QT interval on the ECG is stretched out.

The QT interval measures how long it takes the heart’s ventricles to recharge after each beat. When drugs block the hERG potassium channel, they slow down this recharge. That delay creates an unstable electrical environment where early afterdepolarizations (EADs) can trigger abnormal beats. These beats cascade into TdP, which can either stop on its own-or degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and cause sudden death.

Doctors don’t diagnose TdP by symptoms. Patients might feel palpitations, lightheadedness, or fainting. But in nearly half of cases, there’s no warning at all. The diagnosis is always on the ECG: a prolonged QTc (corrected QT interval) followed by that unmistakable twisting pattern.

Which Medications Cause QT Prolongation?

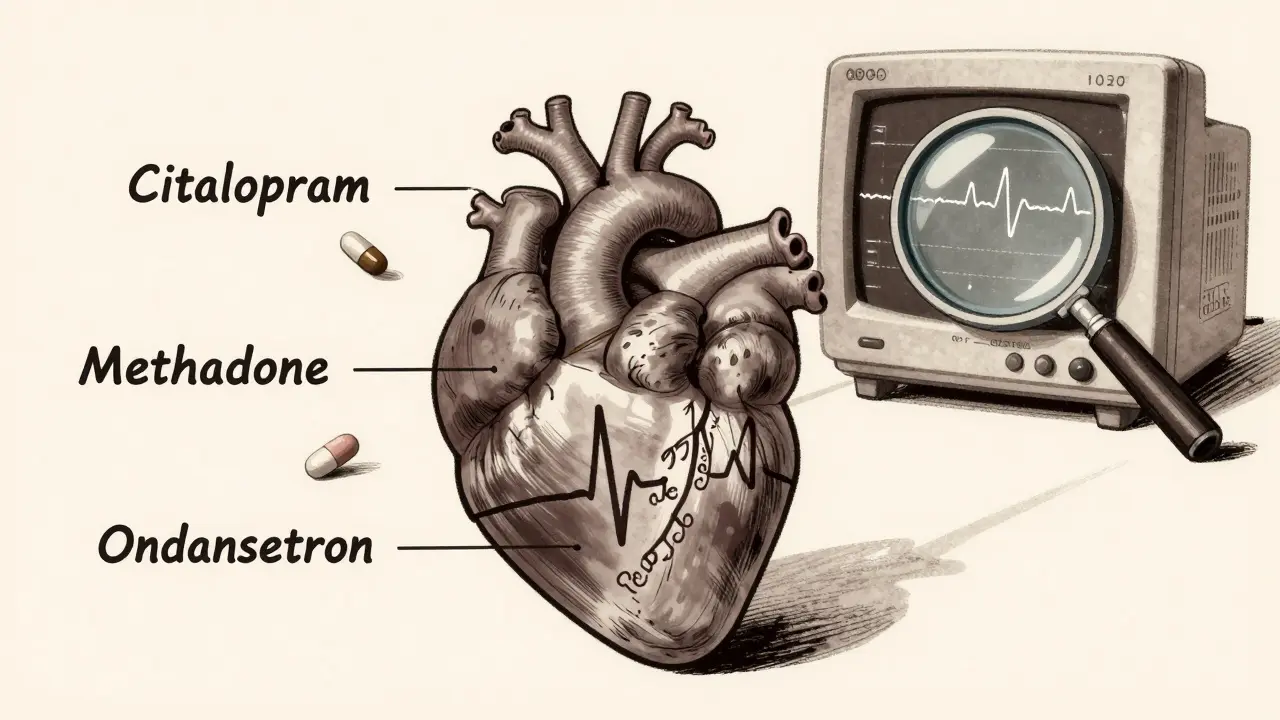

More than 200 commonly prescribed drugs can prolong the QT interval. It’s not just the old-school culprits like quinidine or sotalol. Today, the biggest risks come from everyday prescriptions:

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin, clarithromycin, moxifloxacin

- Antidepressants: Citalopram, escitalopram (especially above 20 mg/day in older adults)

- Antipsychotics: Haloperidol, ziprasidone, thioridazine

- Antiemetics: Ondansetron (especially IV doses over 16 mg)

- Heart meds: Dofetilide, quinidine, procainamide

- Opioid replacement: Methadone (risk spikes above 100 mg/day)

- Antifungals: Ketoconazole, voriconazole

The CredibleMeds database classifies these drugs into three tiers: Known Risk, Possible Risk, and Conditional Risk. Drugs like methadone and citalopram are in the Known Risk group-meaning there’s solid evidence they’ve caused TdP. Others, like azithromycin, fall into Possible Risk-the danger is real but small, and usually only when other factors line up.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about the person taking it. TdP doesn’t strike randomly. It strikes people with a perfect storm of risk factors:

- Women: 70% of TdP cases occur in women-even though men and women have similar QT prolongation rates.

- Age over 65: Nearly 7 out of 10 cases happen in older adults.

- Low potassium: Found in 43% of cases. Levels below 3.5 mmol/L triple the risk.

- Low magnesium: Present in 31% of cases. Levels under 1.6 mg/dL raise risk by nearly 3 times.

- Slow heart rate: Bradycardia (under 60 bpm) is seen in over half of cases.

- Multiple QT drugs: Taking two or more QT-prolonging meds increases risk by 28%.

- Heart disease: 41% of patients have pre-existing heart conditions.

- Renal or liver problems: Impaired clearance leads to drug buildup. Citalopram, for example, becomes 4.8 times riskier in patients with severe kidney disease.

People with inherited long QT syndrome-like Romano-Ward syndrome-are especially vulnerable. Even a single dose of a common antibiotic can trigger TdP in them.

How to Prevent It Before It Starts

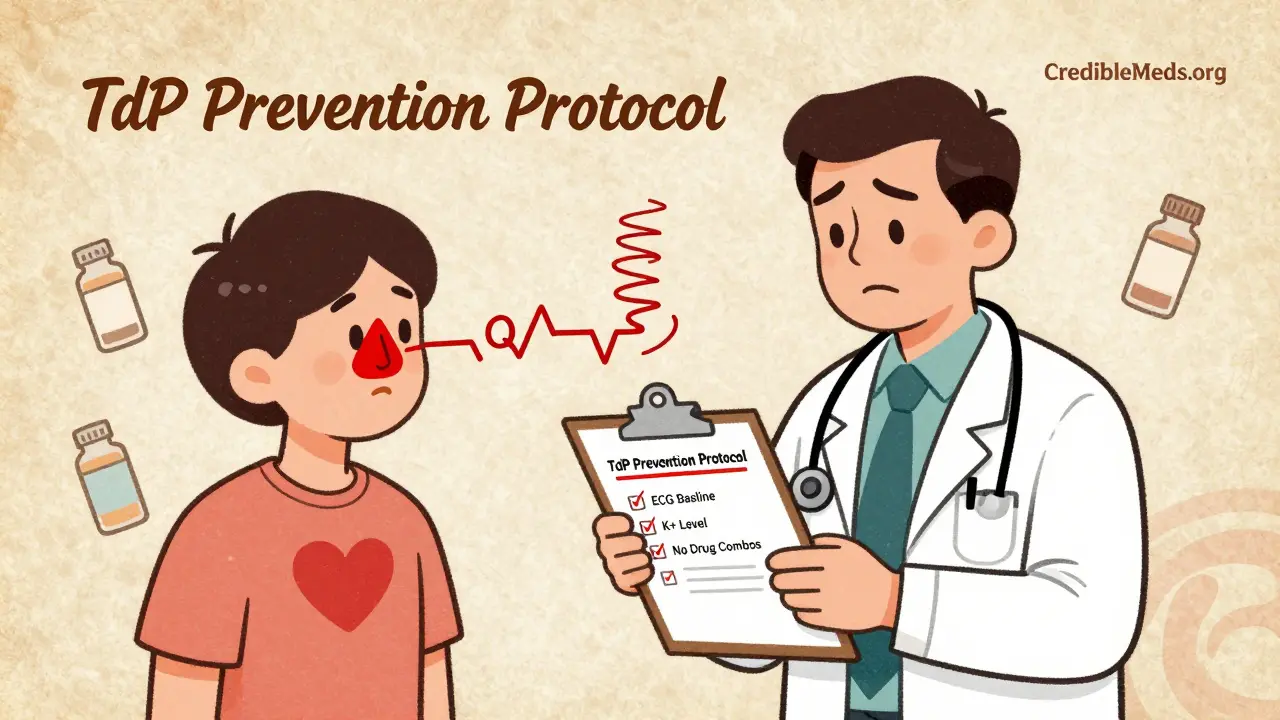

The best way to stop TdP is to never let it happen. Here’s how:

- Check the QTc before prescribing. Get a baseline ECG for anyone starting a high-risk drug. A QTc over 450 ms in men or 460 ms in women is a red flag. Over 500 ms? That’s a hard stop.

- Review every medication. Use CredibleMeds.org to check if a drug is on the list. Don’t assume a drug is safe just because it’s common. Many doctors don’t realize that ondansetron or citalopram can be dangerous.

- Fix electrolytes first. If potassium is below 4.0 mmol/L or magnesium below 2.0 mg/dL, correct them before giving any QT-prolonging drug. This alone cuts risk dramatically.

- Avoid combinations. Never give two drugs from the "Known Risk" list together. Even one "Known" and one "Possible" can be risky.

- Watch the dose. Citalopram should never exceed 40 mg/day, and only 20 mg if the patient is over 60. Methadone doses above 100 mg/day require mandatory ECG monitoring.

- Screen for congenital LQTS. If someone has unexplained fainting, seizures, or family history of sudden death, use the Schwartz score to assess genetic risk.

VA Healthcare data from 2018 to 2022 showed that following these steps reduced TdP cases by 78%. That’s not theory-that’s real-world results.

What to Do If TdP Happens

If a patient goes into TdP, time is everything. The goal is to stop the arrhythmia before it turns into cardiac arrest.

- Give magnesium sulfate. 1 to 2 grams IV over 5 to 10 minutes. It works in 82% of cases-even if magnesium levels are normal. This is the first-line treatment.

- Pace the heart. Temporary pacing to keep the heart rate above 90 bpm shortens the QT interval and stops the arrhythmia. It’s successful in 76% of cases.

- Correct electrolytes. Push potassium and magnesium if levels are low.

- Use isoproterenol if needed. This is a second-line option if pacing isn’t available. It increases heart rate and shortens repolarization.

- Stop the offending drug. Immediately discontinue any QT-prolonging medication.

Defibrillation is only needed if TdP degenerates into ventricular fibrillation. But magnesium and pacing often stop it before it gets that far.

The Bigger Picture: Regulation and Future Tools

The pharmaceutical industry now has to test every new drug for QT prolongation. Since 2005, the ICH E14 guidelines require a "thorough QT study" for every new chemical entity. That’s added over $1 million and 6 to 8 months to drug development.

The FDA has pulled 12 drugs off the market because of TdP risk-like terfenadine (Seldane) and cisapride (Propulsid). Thirty-seven others carry black box warnings, including haloperidol and methadone.

New tools are emerging. Mayo Clinic developed a machine learning model that predicts individual TdP risk with 89% accuracy by analyzing 17 clinical factors. The TENTACLE registry, tracking 15,000 patients, is refining risk thresholds-early data suggests that a QTc over 520 ms with a delta increase of more than 70 ms from baseline has a 94% chance of predicting TdP.

And there’s momentum for change. The 2022 PREVENT TdP Act proposed standardized ECG monitoring protocols. If passed, it could prevent 185 to 270 deaths per year.

Bottom Line: Don’t Fear the Drug-Fear the Oversight

TdP isn’t a mystery. It’s a failure of vigilance. The drugs aren’t inherently evil. The risk is small-about 4 per million women, 2.5 per million men. But when you stack on low potassium, old age, kidney disease, and multiple meds, that small risk becomes a real threat.

The solution isn’t to avoid all QT-prolonging drugs. It’s to use them wisely. Check the ECG. Check the labs. Check the list. Correct what you can. Monitor what you must.

Every time a doctor prescribes citalopram without checking potassium, or gives ondansetron to a frail elderly patient without an ECG, they’re playing Russian roulette with a heart that might not come back.

Prevention isn’t complicated. It’s just systematic. And in medicine, that’s often the difference between life and death.

Can Torsades de Pointes happen without any known risk factors?

Yes, but it’s rare. Most cases involve at least one modifiable risk factor like low potassium, slow heart rate, or multiple QT-prolonging drugs. However, people with undiagnosed congenital long QT syndrome can develop TdP even with a single dose of a low-risk drug. That’s why a personal or family history of unexplained fainting, seizures, or sudden cardiac death should always raise suspicion.

Is a prolonged QT interval always dangerous?

No. A QTc between 450-499 ms in men or 460-499 ms in women is prolonged but carries low risk. Danger increases sharply when QTc exceeds 500 ms or increases by more than 60 ms from baseline. Many people have mildly prolonged QT intervals due to genetics or medication and never have problems. The key is context: the higher the QTc and the more risk factors present, the greater the danger.

Can I take azithromycin if I’m on citalopram?

It’s not recommended. Both drugs prolong the QT interval. Azithromycin is in the "Possible Risk" category, and citalopram is "Known Risk." Combining them increases the chance of TdP, especially in older adults or those with kidney issues. If you need an antibiotic while on citalopram, ask about alternatives like amoxicillin or doxycycline that don’t affect the QT interval.

Do all antidepressants cause QT prolongation?

No. Citalopram and escitalopram are the main culprits among SSRIs. Sertraline and fluoxetine have minimal QT effects. Among SNRIs, venlafaxine carries low risk, while duloxetine is generally safe. Tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline can also prolong QT, so they’re avoided in high-risk patients. Always check CredibleMeds for specific drug profiles.

Why is magnesium given even if levels are normal?

Magnesium stabilizes the heart’s electrical activity independently of serum levels. It reduces early afterdepolarizations-the triggers for TdP-by blocking calcium channels and enhancing potassium flow. Even patients with normal magnesium benefit from IV magnesium during acute TdP. It’s a fast, safe, and effective intervention that doesn’t rely on lab values.

How often should ECGs be repeated when taking methadone?

For methadone, get a baseline ECG before starting. Repeat it 5-7 days after initiation or any dose increase. After that, monitor every 3 to 6 months if the dose is stable. If the dose goes above 100 mg/day, monthly ECGs are recommended. Also repeat the ECG if new symptoms like dizziness or palpitations appear, or if other QT-prolonging drugs are added.

Are there any new drugs that are safer for the heart?

Yes. Newer antipsychotics like aripiprazole and lurasidone have very low QT prolongation risk. Newer antibiotics like levofloxacin carry less risk than moxifloxacin. In antidepressants, sertraline and escitalopram (at low doses) are preferred over citalopram. The trend in drug development is toward agents that avoid hERG channel blockade. Always ask your pharmacist or provider if a newer, safer alternative exists.

12 Comments

kabir das

January 29, 2026 at 05:54

This is insane. Seriously. I had a friend on methadone, citalopram, and ondansetron-all at once-and he collapsed at Target. No warning. Just... gone. They said it was "unexplained." But we knew. We knew. And now? I check every script. Every. Single. One.

Megan Brooks

January 30, 2026 at 10:49

The data here is exceptionally clear. What stands out is not the drugs themselves, but the systemic failure to integrate basic clinical safeguards into routine prescribing. A baseline ECG and electrolyte panel should be as standard as checking blood pressure before initiating any QT-prolonging agent. The fact that this isn't universal is a reflection of fragmented care, not medical ignorance.

Paul Adler

January 30, 2026 at 13:36

I’ve seen this play out in the ER too many times. A 72-year-old woman on citalopram, ondansetron for nausea, and low potassium from diuretics. No one connected the dots. She survived because a nurse noticed the ECG. But how many don’t? We need mandatory alerts in EHRs-not just for high-risk combos, but for low potassium in elderly patients on any QT drug. It’s not rocket science.

Robin Keith

January 30, 2026 at 23:00

You know what’s really tragic? That we’re still having this conversation in 2025. We’ve had the CredibleMeds database for over a decade. We’ve had the ICH E14 guidelines since 2005. We’ve had case reports going back to the 90s. And yet, here we are-still treating cardiac arrest as an "unforeseen complication" rather than the predictable endpoint of a cascade of preventable oversights. It’s not just negligence-it’s a cultural pathology in medicine that prioritizes speed over safety, convenience over consequence.

Sheryl Dhlamini

February 1, 2026 at 05:18

I cried reading this. My mom died from TdP. She was on methadone for chronic pain, took an OTC antacid with magnesium (which she thought was "safe"), and was given ondansetron for chemo nausea. No ECG. No labs. No one asked if she had fainting spells as a teen. They said it was "sudden cardiac death." But it wasn’t sudden. It was silent. And it was avoidable.

LOUIS YOUANES

February 3, 2026 at 04:19

Honestly? I don’t trust any doctor who doesn’t check QTc before prescribing citalopram or methadone. If your provider doesn’t know what CredibleMeds is, find a new one. This isn’t hyperbole. It’s survival. And if you’re on one of these meds, ask for your last QTc. If they don’t know, you’re being played.

Andy Steenberge

February 3, 2026 at 08:53

This is one of the most important posts I’ve read in years. I’m a pharmacist and I see this every day. Patients think "it’s just an antibiotic" or "it’s just an antidepressant." But when you stack them-especially with age, kidney issues, or low potassium-it’s like lighting a fuse. I always run a CredibleMeds check before dispensing. I’ve stopped 17 prescriptions this year alone because of combos. It’s not my job to be the bad guy. But it is my job to keep people alive.

rajaneesh s rajan

February 4, 2026 at 09:05

So we’re supposed to be scared of citalopram but not scared of sugar? Of alcohol? Of stress? Of sleep deprivation? All of those prolong QT too. But no one’s banning coffee or telling old folks to stop eating bananas. This feels like medical fearmongering dressed up as science.

Alex Flores Gomez

February 5, 2026 at 15:57

Lmao at the "78% reduction" stat. That’s from VA data. You think this shit applies to real life? My aunt got on methadone and never had an ECG. She’s 82. Still alive. Probably because she didn’t take the "dangerous" combo. Not because someone checked her potassium. Stop scaring people with stats that don’t mean jack in the real world.

Frank Declemij

February 6, 2026 at 04:18

Magnesium works because it stabilizes the membrane potential. Not magic. Physiology. And yes, it helps even with normal levels. This is basic electrophysiology. If you’re not giving it in TdP, you’re not doing your job.

DHARMAN CHELLANI

February 6, 2026 at 21:15

QT prolongation? Please. Most people with long QT never have TdP. You’re overcomplicating. Just don’t give drugs to old people. Done.

Ryan Pagan

February 7, 2026 at 04:45

This is the kind of post that saves lives. I’m a resident and I used to think TdP was a rare footnote. Now? I check every QTc like it’s my own heartbeat. I tell patients: "If you’re on methadone or citalopram, I need your last ECG. If you don’t have one, we get one today." I’ve had nurses thank me. I’ve had patients cry. This isn’t just medicine. It’s moral responsibility. Thank you for writing this.