Zidovudine and How Patient Advocacy Changed HIV Treatment

When zidovudine first hit the market in 1987, it wasn’t just a new drug-it was the only thing standing between many people with HIV and death. But here’s the truth: zidovudine didn’t save lives because it was perfect. It saved lives because patients refused to let it be the only option.

The first drug that gave people hope

Zidovudine, also known as AZT, was the first antiretroviral approved by the FDA to treat HIV. Developed by Burroughs Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline), it worked by blocking reverse transcriptase, an enzyme HIV needs to copy itself. In early clinical trials, it showed a small but real drop in viral load and a slight increase in survival time. For people facing a death sentence, even a few extra months felt like a miracle.

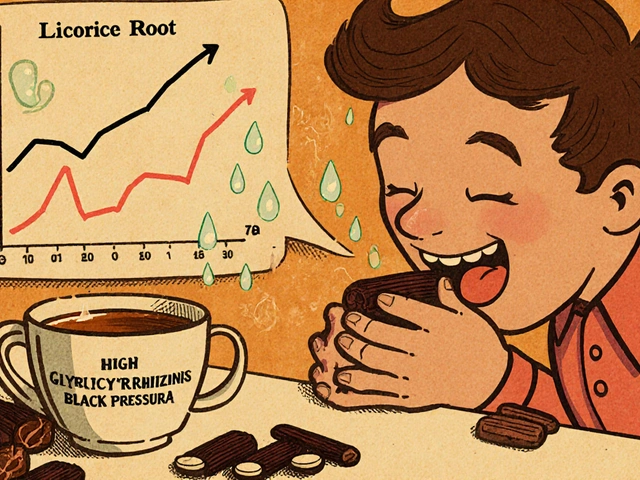

But the reality was messier. Zidovudine came with brutal side effects-severe anemia, nausea, muscle weakness, and fatigue. Many patients couldn’t tolerate the doses. And because it was the only drug available, doctors had no choice but to prescribe it, even when patients were suffering.

At the time, the medical establishment treated HIV like a public health crisis to be managed from above. Patients were passive recipients of care. But that changed fast.

Activists didn’t wait for permission

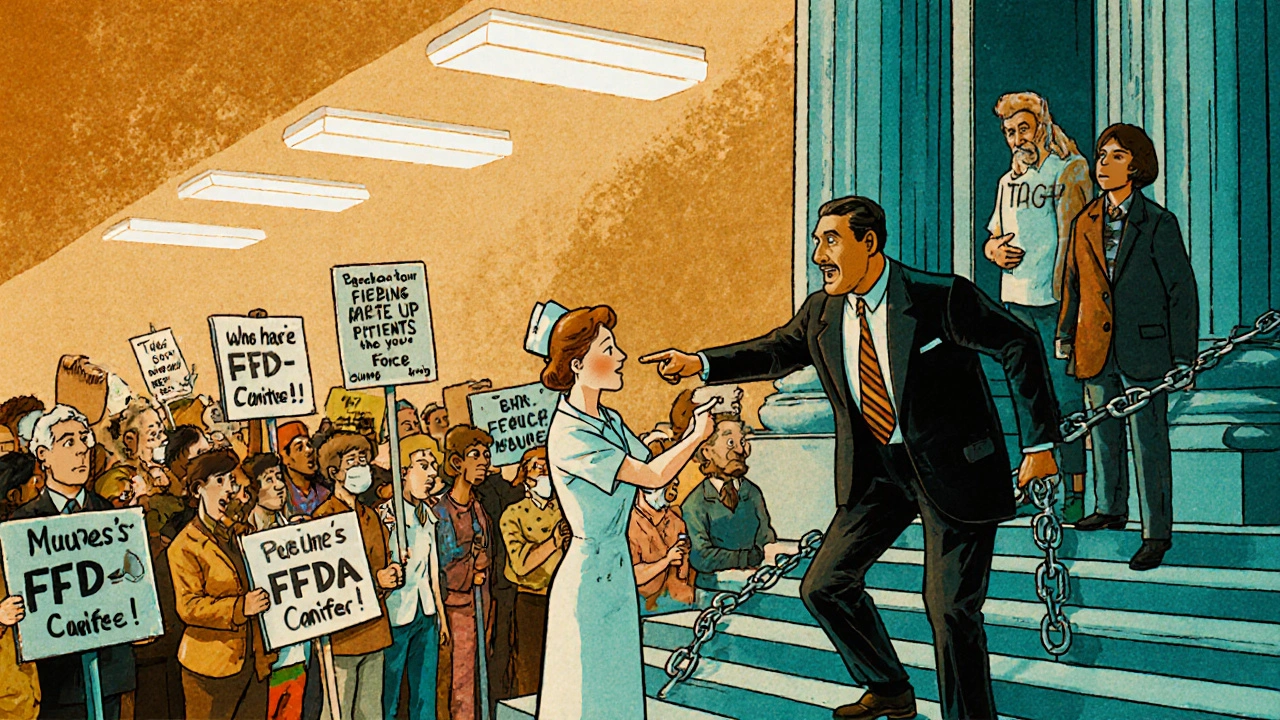

In New York, San Francisco, and Washington D.C., people with HIV-many of them gay men, drug users, and sex workers-started organizing. Groups like ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) didn’t ask for a seat at the table. They stormed the FDA, chained themselves to the White House gates, and interrupted press conferences.

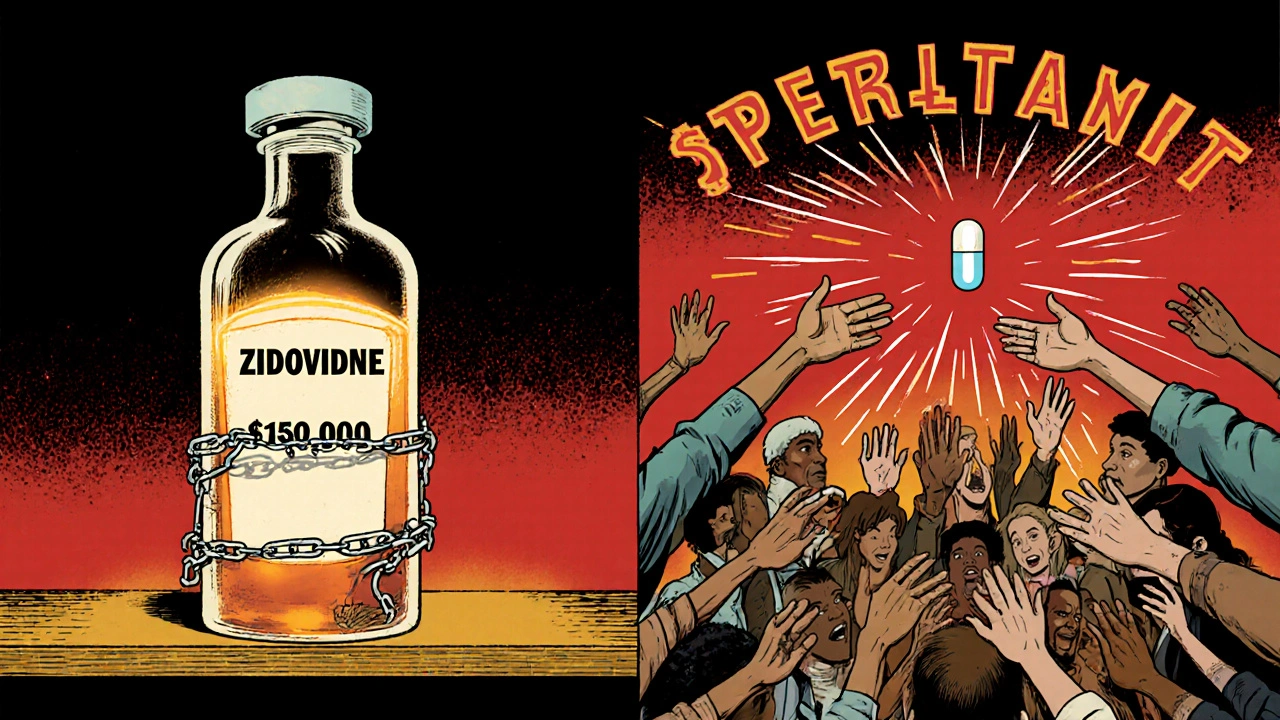

They knew zidovudine wasn’t enough. They knew the drug was priced at $10,000 a year-more than most people earned. They knew the FDA’s approval process was slow, designed for cancer drugs, not a rapidly spreading epidemic. So they demanded faster trials, lower prices, and access to experimental drugs before they were fully approved.

In 1988, ACT UP staged a protest at the FDA’s headquarters. Hundreds showed up. One woman, a nurse with HIV, stood up during a meeting and said, “You’re killing us with your bureaucracy.” The room went silent. A week later, the FDA changed its rules to allow expanded access to unapproved drugs for people with life-threatening conditions.

Zidovudine didn’t become better because scientists improved it. It became more accessible because patients forced the system to listen.

How patient voices reshaped drug development

Before zidovudine, clinical trials were run by doctors for doctors. Patients weren’t consulted about side effects, dosing schedules, or what outcomes mattered most. Was it just about living longer? Or was it about being able to eat, work, or hold your child without vomiting?

Activists pushed for patient-centered outcomes. They demanded that trials measure quality of life, not just survival. They insisted that people with HIV be included in designing trials-not just as subjects, but as advisors.

By the early 1990s, the FDA began including patient advocates on advisory panels. Drug companies started partnering with advocacy groups to design more humane trials. Zidovudine became the first drug where patient feedback directly influenced how it was prescribed.

One woman in Atlanta, diagnosed with HIV in 1989, told her doctor she couldn’t take the full dose because she was a single mother and needed to be awake to care for her kids. Her doctor, moved by her honesty, started titrating doses based on tolerance-not just lab numbers. That kind of individualized care became standard because patients spoke up.

Zidovudine’s legacy isn’t just in the pill

Zidovudine is rarely used alone today. Modern HIV treatment combines three or more drugs-called combination antiretroviral therapy (cART)-to suppress the virus and prevent resistance. Zidovudine is now mostly found in fixed-dose combinations like Combivir or Trizivir, and even then, it’s often replaced by newer, safer drugs like tenofovir or emtricitabine.

But its real legacy isn’t in the pharmacy. It’s in the way we think about medicine.

Before zidovudine, patients were expected to trust doctors without question. After zidovudine, patients learned they had the right to challenge, to demand, to co-create care. The model of top-down medical authority cracked open-and it never closed again.

Today, when someone with HIV asks for a second opinion, when they join a clinical trial to test a new drug, when they speak at a drug company’s patient advisory board-they’re following a path paved by the people who refused to accept silence.

What zidovudine teaches us about power in healthcare

Drug companies don’t lower prices because they’re nice. Regulators don’t speed up approvals because they’re efficient. Change happens when people organize.

The fight over zidovudine wasn’t just about one drug. It was about who gets to decide what’s acceptable in medicine. Was it okay to let people die slowly because the system moved too slowly? Was it okay to charge $10,000 for a pill that kept you alive for a year?

Activists said no. And they won.

Today, we have dozens of HIV drugs. We have PrEP to prevent infection. We have treatments that let people live long, healthy lives. But none of that would have come as fast-or as fairly-if patients hadn’t forced the system to change.

Zidovudine was the spark. Patient advocacy was the flame.

Why this still matters today

Look at the cost of modern HIV drugs. Even with insurance, co-pays can hit $500 a month. In rural areas, people still skip doses because they can’t afford transportation to clinics. Transgender patients face discrimination when seeking care. Black and Latino communities still have higher rates of late diagnosis.

The same power imbalances that existed in 1987 still exist today. But so does the playbook.

Patients are still organizing. Groups like the AIDS Foundation, the National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors, and local peer networks are pushing for generic drugs, better insurance coverage, and culturally competent care.

Every time someone speaks up at a hospital meeting, signs a petition for drug pricing reform, or shares their story with a lawmaker-they’re continuing the work started by those who demanded zidovudine.

You don’t need to be a scientist to change medicine. You just need to refuse to stay quiet.

Is zidovudine still used today for HIV treatment?

Zidovudine is rarely used alone anymore. It’s mostly found in combination pills like Combivir or Trizivir, which pair it with other antiretrovirals. Today’s first-line treatments favor newer drugs like tenofovir and emtricitabine because they’re better tolerated and have fewer side effects. But zidovudine is still used in certain cases-like preventing mother-to-child transmission during pregnancy or when other drugs aren’t available.

What were the major side effects of zidovudine?

Zidovudine caused severe anemia, low white blood cell counts, nausea, vomiting, headaches, and muscle weakness. Some patients developed lactic acidosis, a rare but dangerous buildup of acid in the blood. These side effects were so intense that many people had to stop taking it, even though it was the only option. That’s why patient advocacy pushed for lower doses and better monitoring-leading to safer use protocols.

How did patient advocacy change the FDA’s approval process?

Before the HIV crisis, the FDA required long, rigid trials for drug approval. ACT UP and other groups demanded faster access for dying patients. Their protests led to the creation of the Expanded Access Program in 1987, which let patients use unapproved drugs outside clinical trials. They also pushed for patient input in trial design and outcome measures. These changes became permanent parts of how the FDA evaluates drugs today.

Why was zidovudine so expensive in the 1980s?

Burroughs Wellcome priced zidovudine at $10,000 per year-more than the average American’s annual income. The company claimed it needed to recoup research costs. But activists proved the drug’s actual production cost was under $200 a year. Protests, lawsuits, and public pressure forced the company to lower the price by 25% in 1989 and eventually offer discounts to low-income patients.

Can patient advocacy still influence drug access today?

Absolutely. Patient groups today are pushing for lower prices on HIV drugs like Truvada and Descovy, demanding insurance coverage for PrEP, and fighting for access in rural and marginalized communities. They sit on advisory boards for drugmakers, testify before Congress, and use social media to amplify their stories. The same tactics that worked for zidovudine-protests, media campaigns, direct engagement with regulators-are still the most effective tools for change.

10 Comments

Christine Mae Raquid

November 2, 2025 at 02:25

so like... zidovudine was basically the first real shot we had and people still cried about side effects? grow up. if you’re dying, you take the pill. period.

Torrlow Lebleu

November 2, 2025 at 03:01

Let’s be real - this whole ‘patient advocacy’ narrative is just woke revisionism. ACT UP didn’t change the FDA, they just scared them into making rushed decisions that led to worse outcomes down the line. The real breakthrough was combination therapy in the mid-90s, not some guy yelling into a mic at a press conference. Also, $10k a year in 1987? That’s like $28k today. Not exactly a ripoff when you factor in R&D and the fact that no one else was even trying.

And don’t get me started on the ‘pharma is evil’ myth. Glaxo didn’t hoard the drug - they scaled production faster than any company had ever done for a new antiviral. The real villain was the CDC’s refusal to recognize HIV as a human crisis until it was too late for thousands.

Yes, patients demanded change. But demand without data is just noise. The FDA didn’t change because of protests - they changed because researchers finally had enough clinical evidence to justify accelerated approval. The activists didn’t invent science. They just got loud enough that the media couldn’t ignore it.

Also, calling it a ‘spark’? No. It was a spark in a dry forest. The real fire was the collaboration between scientists, clinicians, and yes - even some patient reps - who actually understood pharmacokinetics. Not just people holding signs that said ‘ACT UP’ while ignoring the fact that AZT monotherapy caused mitochondrial toxicity.

Modern HIV treatment didn’t come from protests. It came from peer-reviewed journals, longitudinal studies, and pharmaceutical engineers who didn’t care about your outrage - they cared about half-lives and resistance profiles.

Don’t romanticize chaos. Progress isn’t made by shouting. It’s made by people in lab coats doing the boring, unglamorous work you’d never see on a Netflix documentary.

Sue Ausderau

November 3, 2025 at 09:53

I think about how much courage it took just to breathe in those days. Not just the activism - but the quiet moments too. The woman who took half a pill so she could hold her baby. The man who wrote letters to his future self because he didn’t know if he’d live to see next week. That’s the real legacy. Not the protests. Not the prices. Just people refusing to let fear be the last word.

Tina Standar Ylläsjärvi

November 4, 2025 at 17:35

Thank you for writing this. I’m a nurse who worked in an AIDS ward in ‘92. We didn’t have the drugs we have now. We had AZT, and we had each other. Patients taught us how to listen. One guy told me, ‘I don’t care if it kills me slower - I just want to feel like I’m still alive.’ That changed how we dosed everything after that. You’re right - it wasn’t just the pill. It was the people behind it.

M. Kyle Moseby

November 5, 2025 at 11:35

people were just mad because they had to pay for medicine. that’s not bravery. that’s greed.

Zach Harrison

November 6, 2025 at 04:23

the thing people forget is that the activists weren’t just angry - they were smart. they read the science, they showed up with data, they knew how to talk to reporters. they didn’t just yell - they made the system look bad so it had to change. it’s not magic. it’s strategy. and honestly? we need more of that today.

Terri-Anne Whitehouse

November 7, 2025 at 03:33

It’s amusing how Americans romanticize grassroots activism as some noble, pure force - while ignoring the fact that the entire system was already shifting due to scientific momentum. The FDA’s accelerated approval pathway was in development since 1983. ACT UP didn’t create it; they opportunistically exploited a pre-existing bureaucratic vulnerability. And the pricing? Of course it was high - it was a novel compound with no existing manufacturing infrastructure. The real moral failure was the U.S. government’s refusal to fund public production, not the company’s profit motive.

Also, the notion that ‘patients changed medicine’ is a gross oversimplification. Patients didn’t design the pharmacokinetic models. They didn’t optimize the dosing regimens. They didn’t discover reverse transcriptase inhibitors. They showed up with signs. That’s symbolic. Not structural.

Dave Collins

November 8, 2025 at 12:05

so let me get this straight - we’re supposed to be impressed because people yelled at a government building and suddenly, magic? next they’ll tell us that yelling at your wifi router fixes the internet.

also, $10k a year? cool. so was a new car in 1987. guess what? people bought cars. they also bought AZT. because they wanted to live. not because they were ‘oppressed’ - because it worked. stop turning medical history into a TED Talk.

Idolla Leboeuf

November 9, 2025 at 02:28

they didn’t wait for permission to be human and that’s the whole damn point. if you’re waiting for someone to hand you dignity you’re already dead. the pill was just the vehicle - the real medicine was refusing to be silent

Cole Brown

November 10, 2025 at 00:12

Thank you, Sue. That’s exactly it. It wasn’t just about the drug - it was about being seen. And that’s what still matters today. Every time someone speaks up, even quietly - they’re still walking that path. Keep going.