Absolute Risk vs Relative Risk in Drug Side Effects: How to Interpret the Numbers

Absolute vs Relative Risk Calculator

Enter Risk Values

What Do These Numbers Mean?

When you reduce your risk from 4% to 3%:

- Absolute risk reduction: 1 percentage point

- Relative risk reduction: 25%

- Number Needed to Treat (NNT): 100

This means 100 people need to take the drug for one person to benefit. The other 99 get no benefit but might still have side effects.

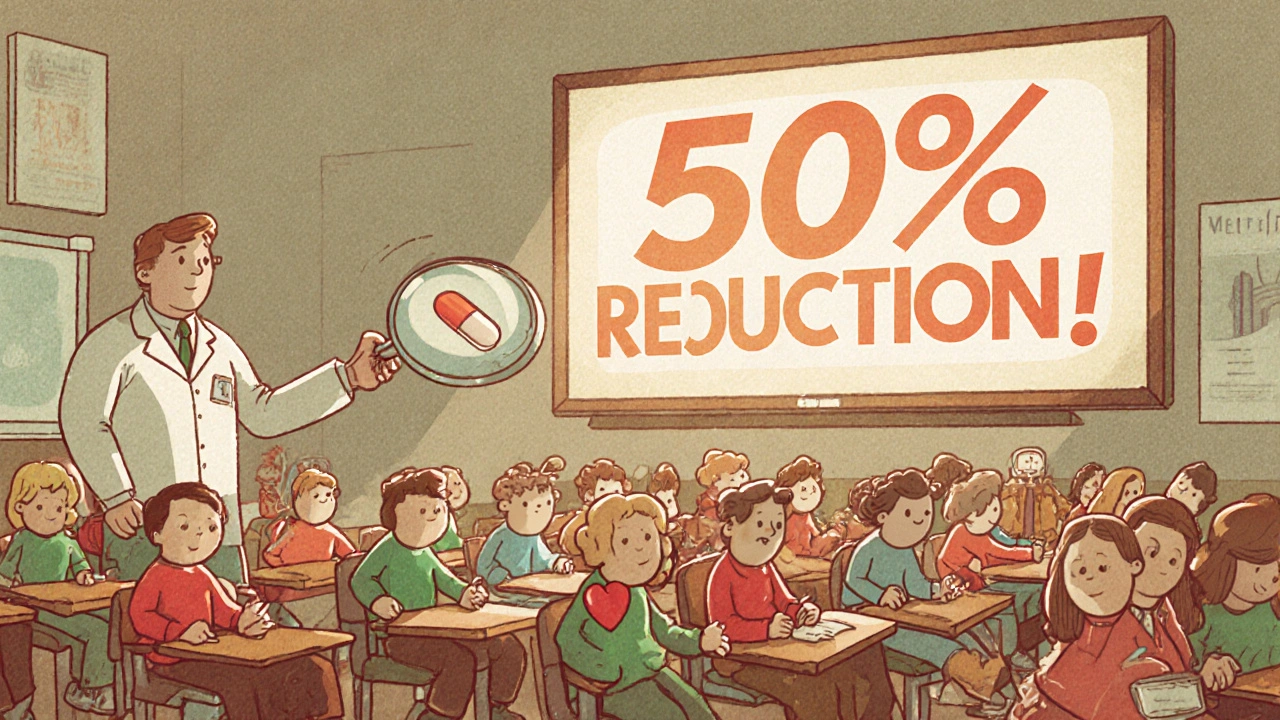

When you hear a drug reduces your risk of a heart attack by 50%, it sounds amazing. But what if your risk was only 2% to begin with? That 50% drop means you’re now at 1%-not a miracle, just a small improvement. This is the gap between absolute risk and relative risk, and understanding it could change how you decide whether to take a medication.

What Absolute Risk Really Means

Absolute risk tells you the actual chance something will happen to you. If 1 in 100 people get a rare side effect from a drug, that’s a 1% absolute risk. It doesn’t compare you to anyone else. It just says: out of 100 people like you, one might have this problem.Let’s say a drug lowers your chance of a stroke from 4% to 3%. The absolute risk reduction is 1 percentage point. That’s it. No multiplication. No fancy percentages. Just a 1% drop in real-world likelihood.

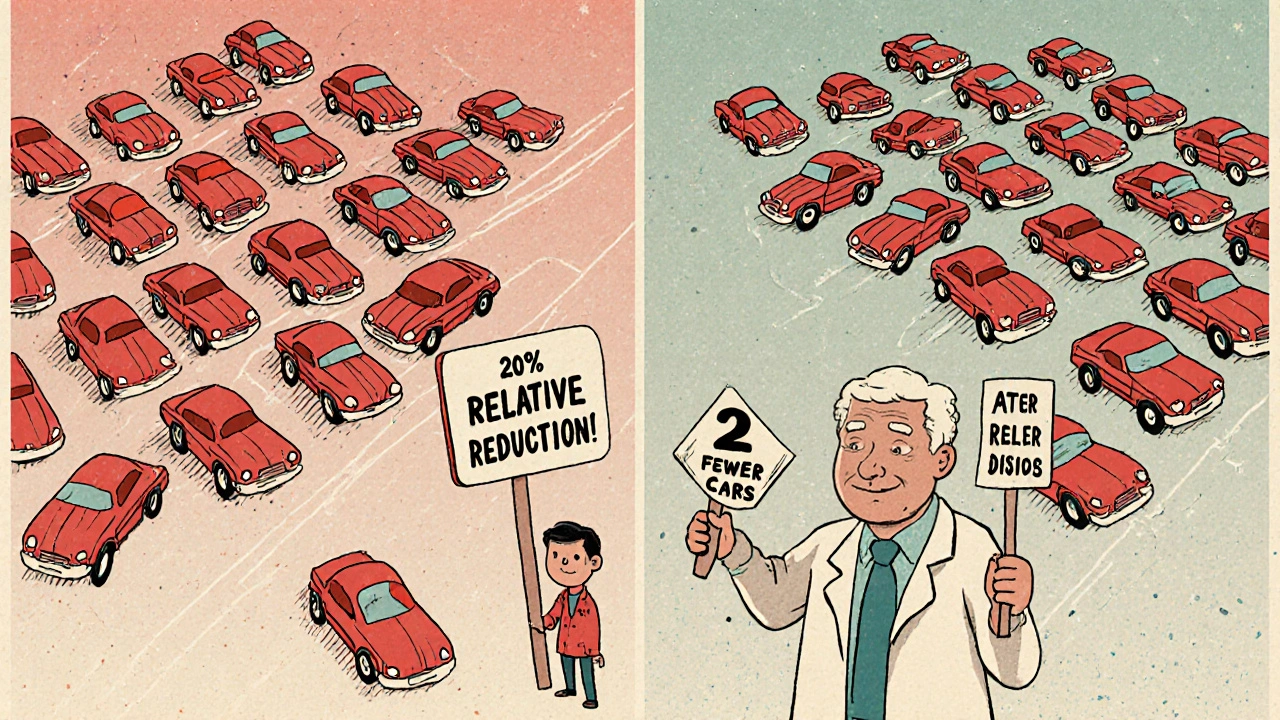

Doctors use absolute risk to answer the question: “How likely is this to affect ME?” It’s personal. It’s concrete. If you’re one of 100 people, and only one gets a side effect, you can picture that. One person out of a classroom. One car in a parking lot of 100. That’s how your brain understands risk.

What Relative Risk Is Trying to Sell You

Relative risk compares two groups: people who took the drug versus those who didn’t. It’s a ratio. If your stroke risk drops from 4% to 3%, the relative risk reduction is 25%. How? Because 1% (the difference) divided by 4% (the original risk) equals 0.25, or 25%.Pharmaceutical ads love this number. 25% sounds better than 1%. But here’s the trick: relative risk doesn’t tell you the starting point. A 50% reduction in risk sounds huge-until you learn the original risk was 0.02%. Then the absolute drop is 0.01%. That’s like going from 2 in 10,000 to 1 in 10,000. You’re still almost certainly not going to have the problem.

This is why you see headlines like “New Drug Cuts Heart Attack Risk by Half!” But if you’re a healthy 30-year-old with a 2% lifetime risk of a heart attack, cutting that in half still leaves you at 1%. That’s not a life-saving breakthrough. It’s a small statistical shift.

Why the Difference Matters in Real Life

Imagine two drugs for high blood pressure. Drug A reduces your chance of a heart attack from 10% to 8%. That’s a 20% relative risk reduction. Drug B reduces it from 2% to 1%. That’s a 50% relative risk reduction. Which one sounds better?Drug B’s 50% sounds amazing. But Drug A’s 2% absolute reduction means 2 out of every 100 people taking it will avoid a heart attack. Drug B? Only 1 out of every 100 people benefits. The relative risk makes Drug B look superior. The absolute risk tells you Drug A helps more people in real terms.

Same thing with side effects. A drug might increase your risk of nausea by 200%. Sounds scary. But if the baseline risk was 2%, now it’s 6%. That’s 4 extra people out of 100 feeling sick. Not trivial-but not a disaster either. The 200% sounds like a red flag. The absolute increase? Manageable.

The Number Needed to Treat (NNT): The Real Cost of Benefit

There’s a number doctors use to cut through the noise: Number Needed to Treat, or NNT. It tells you how many people need to take a drug for one person to benefit.If a drug reduces heart attack risk from 4% to 3%, the absolute risk reduction is 1%. So NNT = 1 ÷ 0.01 = 100. That means 100 people must take the drug for one person to avoid a heart attack. The other 99 won’t benefit-but might still get side effects.

Compare that to a drug with an NNT of 5. That’s way better. Five people take it, one benefits. That’s a strong signal. But if the NNT is 500? You’re treating 500 people to help one. That’s a weak benefit, even if the relative risk looks good.

NNT is the most honest metric. It doesn’t hide behind percentages. It just says: how many people are you asking to take a pill for one to win?

How Ads Trick You (And Why It’s Legal)

In 2021, a study found 78% of direct-to-consumer drug ads in the U.S. highlighted relative risk reduction-without ever mentioning the absolute risk. That’s not a mistake. It’s strategy.Think about it: a 90% relative risk reduction sounds like a miracle cure. But if the original risk was 0.01%, the absolute drop is 0.009%. You’re talking about going from 1 in 10,000 to 1 in 100,000. That’s not a cure. It’s a tiny statistical tweak.

Meanwhile, side effects? Those are often reported as absolute risks. “1 in 50 people get dizziness.” That’s clear. But the benefit? “Reduces risk by 70%!”-with no context. That’s not misleading. It’s legal. And it works. Drugs marketed with relative risk reductions see 23% higher initial prescriptions.

But here’s the catch: when patients later learn the real numbers, adherence drops by 15%. People feel tricked. And they stop taking the drug.

How to Read the Numbers Yourself

You don’t need a statistics degree. Here’s how to decode what you’re hearing:- Ask for the baseline risk. “What’s my chance of this problem without the drug?”

- Ask for the absolute change. “How much does this lower my risk?”

- Ask for the NNT. “How many people need to take this for one to benefit?”

- Compare side effects the same way. “How many people get this side effect?”

Example: Your doctor says, “This statin cuts your heart attack risk in half.”

You reply: “What’s my current risk?”

They say: “About 2% over the next 10 years.”

You say: “So it drops to 1%?”

They say: “Yes.”

You think: “So out of 100 people like me, 2 would have a heart attack. Now only 1 will. That means 98 people take this drug every day for 10 years, and only one avoids a heart attack. And 20% of people get muscle pain. Is that worth it for me?”

Now you’re making a real decision-not a marketing one.

What Experts Say

Dr. Steve Woloshin and Dr. Lisa Schwartz from Dartmouth have spent decades studying this. They say: “Absolute numbers matter.” If you only hear relative risk, you’re getting half the story. A 50% reduction sounds powerful. But if the absolute risk was 0.1%, you’re talking about 0.05% improvement. That’s not a treatment. That’s noise.The FDA now recommends including both absolute and relative risks in patient materials. But enforcement is weak. Most patient leaflets still bury the absolute numbers.

One study found 60% of doctors can’t correctly convert relative risk to absolute terms. If they’re confused, how are patients supposed to understand?

Visual Aids Help-A Lot

Try this: imagine 100 little people. Each is you. Now color them based on risk.Before the drug: 4 out of 100 are red (heart attack risk). After the drug: 3 out of 100 are red. One person changed color. That’s it.

Now imagine the same 100 people with a side effect: 5 are yellow (nausea). After the drug: 7 are yellow. Two more turned yellow.

That’s the whole story. No percentages. No ratios. Just 100 people. You see the trade-off. That’s why pictograms and risk ladders work better than charts. Your brain gets it.

When Relative Risk Is Actually Useful

Relative risk isn’t useless. It’s great for spotting patterns. If smokers have 20 times the risk of lung cancer, that’s a powerful signal. It helps researchers find causes. But for you? For your decision? Absolute risk is what matters.Think of it like weather forecasts. “There’s a 20% chance of rain” is absolute. “It’s twice as likely to rain today as yesterday” is relative. Which one tells you whether to bring an umbrella? The 20%.

What You Should Do Next

Next time a doctor or ad talks about risk reduction:- Don’t accept “cut in half” or “reduced by 70%” as the full answer.

- Ask: “What’s my starting risk?”

- Ask: “How many people need to take this for one to benefit?”

- Ask: “What’s the absolute increase in side effects?”

Write it down. Compare it. Don’t let numbers scare you or sell you. Understand them.

Medication decisions aren’t about percentages. They’re about people. You’re one person. You deserve to know what that one person’s real chance is-not what the math looks like on a billboard.

What’s the difference between absolute risk and relative risk?

Absolute risk tells you your actual chance of something happening, like a side effect or heart attack. For example, if 2 out of 100 people have a heart attack, your absolute risk is 2%. Relative risk compares your risk to someone else’s. If a drug cuts your risk in half, that’s a 50% relative risk reduction-but if your starting risk was only 2%, now it’s 1%. The absolute change is just 1 percentage point.

Why do drug ads use relative risk instead of absolute risk?

Relative risk numbers are bigger and sound more impressive. A 50% reduction sounds better than a 1% reduction-even if they’re describing the same thing. Drug companies use relative risk because it boosts sales. A 2021 study found 78% of U.S. drug ads used relative risk without showing the absolute numbers, even though that can mislead patients.

What is Number Needed to Treat (NNT)?

NNT tells you how many people need to take a drug for one person to benefit. If a drug reduces heart attack risk from 4% to 3%, the absolute benefit is 1%. So NNT = 1 ÷ 0.01 = 100. That means 100 people must take the drug for one person to avoid a heart attack. The other 99 get no benefit but might still have side effects.

How can I tell if a drug’s benefit is worth the side effects?

Compare the absolute benefit to the absolute risk of side effects. If the drug reduces your heart attack risk from 2% to 1% (1% absolute benefit), but causes nausea in 10% of users (10% absolute risk), you’re trading a small benefit for a common side effect. Ask: “Is a 1% lower chance of a heart attack worth a 1 in 10 chance of feeling sick every day?”

Are there tools to help me understand these numbers?

Yes. Visual tools like pictograms-showing 100 people with colored dots for risk-help more than numbers. Many clinics now use them. You can also find free risk calculators online from trusted sources like the American Heart Association or Mayo Clinic. Always ask your doctor for the absolute numbers, not just percentages.

11 Comments

akhilesh jha

November 24, 2025 at 08:12

Had no idea relative risk was being used like marketing fluff. I read a stat about a new cholesterol drug cutting risk by 40% and thought I was getting a miracle. Turns out my baseline was 1.5% so now it's 0.9%. That’s like going from 3 people in a stadium of 200 to 2. Not life-changing. Just... quiet.

Jeff Hicken

November 25, 2025 at 00:49

lol pharma companies are just out here turning math into clickbait. 'CUTS HEART ATTACK RISK IN HALF!' while ignoring you had a 0.8% chance to begin with. I'm just here waiting for the ad that says 'this pill makes you 0.0001% less likely to sneeze in july'. 😂

Vineeta Puri

November 25, 2025 at 23:19

Thank you for this clear, grounded explanation. Many patients, especially those without medical training, are left feeling overwhelmed or misled by relative risk statistics. I've trained community health workers to always ask for absolute numbers and NNT - it transforms the conversation from fear to informed choice. Knowledge is power, and clarity is compassion.

Victoria Stanley

November 26, 2025 at 04:01

So true! I work in a clinic and we started using those little 100-person pictograms with patients - red dots for risk, yellow for side effects. Suddenly, people get it. One lady said, 'Ohhh, so only ONE of us gets helped? And TWO feel sick?' and she just nodded and said she'd skip it. No pressure. Just truth. More clinics need this.

Alex Dubrovin

November 27, 2025 at 11:09

why do doctors even say 'cut in half' if they know it's misleading? i get it they're busy but come on. if you're gonna tell me something sounds like a miracle you better damn well tell me the whole story

Jacob McConaghy

November 28, 2025 at 12:39

As someone who grew up in a country where meds are sold like candy at the corner store, I can tell you this isn't just an American problem. But here? It's a full-blown industry. I once saw a billboard for a diabetes drug that said '90% reduction in complications!' - no mention that the baseline was 0.5%. That's not marketing. That's manipulation wrapped in a lab coat.

Natashia Luu

November 28, 2025 at 21:11

This is precisely why I refuse to take any new medication unless I’ve seen the actual trial data. Not the press release. Not the pamphlet. The raw numbers. If your doctor can’t provide them, find another one. This isn’t about being difficult - it’s about not being a statistic in someone else’s quarterly report.

Douglas cardoza

November 29, 2025 at 19:41

just read this and immediately thought of my dad. he took that blood pressure pill for 3 years because the ad said 'cuts risk by 50%' then stopped when he found out the NNT was 120. he said 'i'd rather just walk more' and he's been fine. real talk

Adam Hainsfurther

November 30, 2025 at 23:46

the NNT metric is the most underused tool in medicine. if you’re asking 100 people to take a pill for one benefit, that’s not a treatment - it’s a lottery. and we’re all buying tickets without knowing the odds. i wish every prescription came with an NNT sticker on the bottle. like nutritional info.

Rachael Gallagher

December 1, 2025 at 10:21

They profit from your fear. That’s it.

steven patiño palacio

December 2, 2025 at 12:51

I appreciate the clarity here. As a former medical educator, I’ve seen how easily relative risk distorts perception - even among clinicians. The key is not to demonize relative risk, but to always pair it with absolute risk and NNT. Patients deserve transparency, not sales pitches. I’ve started including pictograms in all my patient handouts. The difference in understanding is immediate and profound. Thank you for advocating for better communication.