Liver Transplantation: Eligibility, Surgery, and Immunosuppression Explained

When your liver fails, there’s no backup. No second chance. No pill that can replace its work. For people with end-stage liver disease, a liver transplant isn’t just an option-it’s the only thing that can bring them back to life. But it’s not simple. It’s not quick. And it doesn’t end when the surgery is over. Understanding who qualifies, what happens during the operation, and how the body is kept from rejecting the new organ is critical for patients and families facing this journey.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

Not everyone with liver disease gets on the transplant list. The system is strict because organs are scarce. In the U.S., about 8,000 liver transplants happen each year, but over 10,000 people are waiting. So who makes the cut? The first thing doctors look at is the MELD score-Model for End-Stage Liver Disease. It’s calculated from three blood tests: bilirubin, creatinine, and INR. The higher the score, the sicker you are. Scores range from 6 to 40. Someone with a MELD of 35 is in critical condition and moves to the top of the list. Someone with a MELD of 10 might wait months or years. But MELD isn’t the whole story. If you have liver cancer, you have to meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors, all under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor is bigger or has invaded blood vessels, you’re not eligible unless you respond to treatment and bring your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels down below 500. Even then, it’s reviewed case by case. Then there’s the psychosocial side. Do you have someone to help you after surgery? Do you have stable housing? Are you able to take medications exactly as prescribed? If you’ve struggled with alcohol or drugs, most centers require at least six months of sobriety. But that rule isn’t the same everywhere. Some centers now accept three months if you’re in a strong support system. A 2023 study from Yale showed no difference in survival between patients with three versus six months of abstinence. And here’s something many don’t realize: you can’t be too overweight. Donors for living transplants must have a BMI under 30. Recipients with severe obesity often face higher surgical risks and are sometimes delayed until they lose weight. Mental health matters too. Depression, untreated anxiety, or poor insight into the need for lifelong care can disqualify someone.The Surgery: What Happens Inside the Operating Room

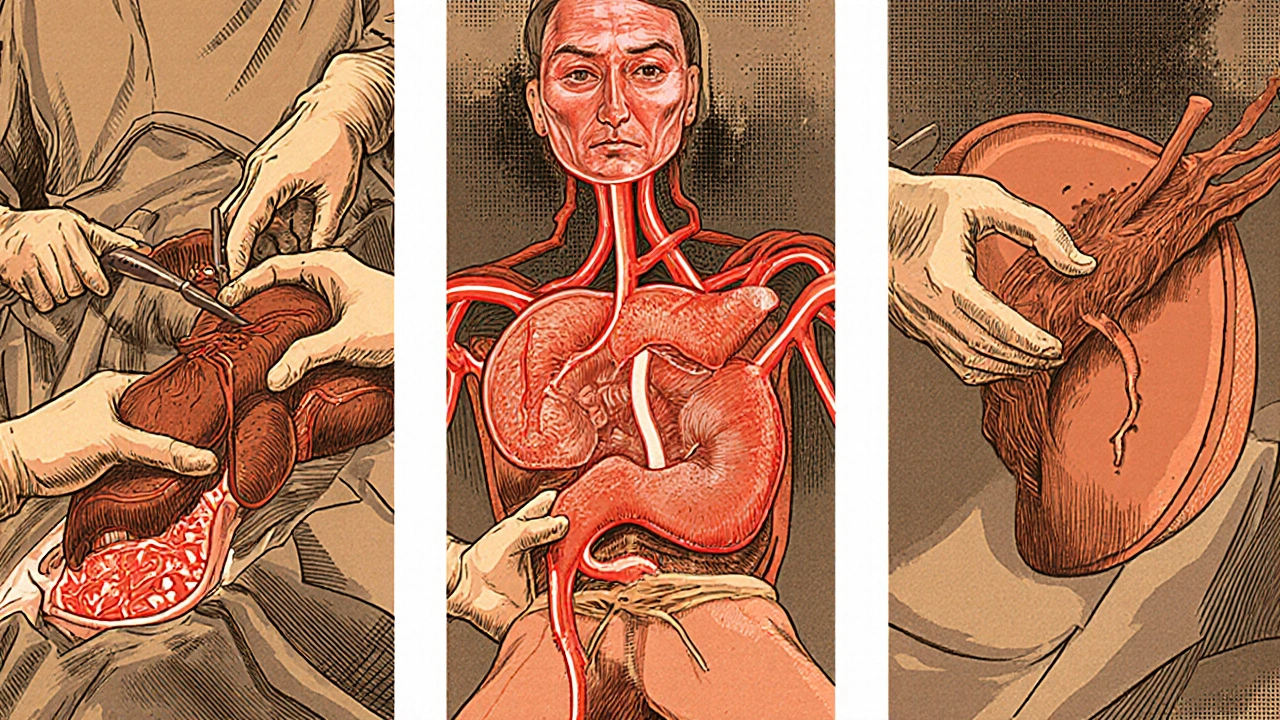

A liver transplant takes between six and twelve hours. It’s not one procedure-it’s three. First, the hepatectomy: the diseased liver is carefully removed. Surgeons cut away connections to blood vessels and bile ducts. This is the most delicate part. One mistake, and you risk massive bleeding. Then comes the anhepatic phase. For the first time in your life, you have no liver. Your body can’t filter toxins, make proteins, or process nutrients. This phase lasts 1-3 hours. Blood pressure drops. Fluids are pushed in. The surgical team watches every number closely. Finally, the implantation: the new liver is sewn in. The most common technique today is the piggyback method, where the recipient’s inferior vena cava (the main vein returning blood to the heart) is kept intact. This reduces blood loss and complications. About 85% of transplants use this method. For living donors, things are even more complex. A healthy person donates part of their liver-usually the right lobe (55-70%) for adults, or the left lateral segment for children. The liver regenerates in both donor and recipient. Donors typically stay in the hospital for 7-10 days and need 6-8 weeks to recover fully. The risk of death for donors is low-about 0.2%-but complications like bile leaks or infections happen in 20-30% of cases. New tech is helping. The FDA approved a portable liver perfusion device in 2023 that keeps donor livers alive outside the body for up to 24 hours. This gives surgeons more time to assess quality and reduces damage from cold storage. Centers using this tech report fewer biliary complications, especially with livers from donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Balancing Act

Your body sees the new liver as an invader. Without drugs to stop it, your immune system will destroy it within days. That’s where immunosuppression comes in. Right after surgery, most patients get induction therapy. Low-risk patients get basiliximab-two IV doses on days 0 and 4. High-risk patients (those with prior transplants, infections, or high antibody levels) get anti-thymocyte globulin over five days. Then comes maintenance: a triple-drug combo. Most centers use:- Tacrolimus: taken twice daily. Blood levels are checked weekly at first. Target is 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then lowered to 4-8 ng/mL. Too high? Kidney damage. Too low? Rejection.

- Mycophenolate mofetil: 1,000 mg twice a day. Stops immune cells from multiplying. Side effects: nausea, diarrhea, low white blood cell count.

- Prednisone: starts at 20 mg a day, then tapers down to 5 mg by three months. Many centers now skip it after the first month. Steroid-free protocols have cut diabetes risk from 28% to 17%.

- 35% of patients have kidney damage from tacrolimus

- 25% develop diabetes

- 20% experience tremors or trouble sleeping

- 30% have ongoing stomach issues from mycophenolate

- 10% get bone marrow suppression

Living vs. Deceased Donors: The Real Trade-Offs

You can get a liver from a deceased donor-or from a living person. Living donor transplants cut waiting time dramatically. In high-MELD patients, the wait for a deceased donor can be over a year. With a living donor, surgery can happen in as little as three months. But it’s not risk-free for the donor. Complication rates are 20-30%. Some donors have bile duct strictures or chronic pain. A few need additional surgery. Deceased donor livers come from two sources: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). DCD livers-where the heart stops before organ recovery-used to be considered risky. They had higher rates of bile duct problems (25% vs. 15% for DBD). But now, with machine perfusion, those rates have dropped to 18%. Five-year survival is nearly the same: 68% for DCD, 72% for DBD. Geography matters too. If you live in California (OPTN Region 9), you might wait 18 months for a liver with a MELD of 25-30. In the Midwest (Region 2), the same patient waits 8 months. That’s not a glitch-it’s how the system is organized.

9 Comments

LINDA PUSPITASARI

December 1, 2025 at 00:49

Just had my brother get a transplant last year 🥹 MELD was 38 when he got the call. We cried for an hour straight. The waiting game is brutal but this post nailed it. Don’t forget to thank your liver. It’s been working overtime your whole life 💪❤️

Mary Kate Powers

December 2, 2025 at 04:23

I work in transplant coordination and I can’t tell you how many families think the surgery is the end. It’s really just the beginning. The meds, the blood draws, the fear of missing a dose - it’s a full-time job. But seeing someone walk out of here six months later, eating pizza and laughing with their grandkids? Worth every second.

Steven Howell

December 2, 2025 at 21:44

It is imperative to underscore the extraordinary complexity inherent in the procurement, preservation, and implantation of hepatic grafts. The piggyback technique, while statistically superior in reducing intraoperative hemorrhage, demands a level of surgical precision that is not universally available. Furthermore, the ethical implications of living donor transplantation warrant rigorous institutional oversight and longitudinal psychosocial follow-up.

Bernie Terrien

December 4, 2025 at 07:40

Let’s be real - the system’s rigged. Rich folks get liver slots faster because they’ve got private docs pushing their MELD. Poor folks? They’re stuck waiting while some CEO in Texas gets a DCD liver from a 22-year-old bike crash victim. And don’t even get me started on how they treat addicts like criminals instead of patients.

Jennifer Wang

December 5, 2025 at 14:38

Regarding immunosuppressive regimens, the trend toward steroid avoidance is supported by multiple meta-analyses demonstrating reduced incidence of new-onset diabetes mellitus and improved metabolic profiles. However, the long-term renal toxicity associated with calcineurin inhibitors remains a significant concern, necessitating individualized dosing strategies based on therapeutic drug monitoring.

stephen idiado

December 7, 2025 at 11:43

Organ trafficking is real. You think this is science? It’s a black market with hospital logos. They’re harvesting organs from undocumented immigrants. The ‘donor’ stories? Fabricated. MELD scores? Manipulated. Wake up.

Subhash Singh

December 8, 2025 at 17:09

Could you please elaborate on the criteria utilized by different OPTN regions for prioritizing patients with MELD scores between 25 and 30? Additionally, is there any published data comparing graft survival rates between DCD and DBD donors when perfusion technology is employed?

Geoff Heredia

December 9, 2025 at 21:49

Did you know the FDA approved that perfusion machine right after the CDC quietly changed the definition of ‘brain death’? They’re hiding something. The liver isn’t ‘alive’ in the machine - it’s being kept alive by quantum resonance tech from DARPA. You think they’d let you keep a dead organ alive for 24 hours? That’s not medicine. That’s control.

Tina Dinh

December 10, 2025 at 12:47

TO THE PERSON WHO JUST GOT THEIR LIVER - YOU GOT THIS 💪🫶 I know it’s scary but you’re stronger than you think. Every pill, every blood test, every scary symptom - you’re fighting for your next birthday. And you’re gonna make it. I believe in you. 🌟