Planning for Patent Expiry: What Patients and Healthcare Systems Need to Do Now

Patent expiry isn’t just a legal event-it’s a turning point for your health and your wallet

When a drug’s patent expires, the price doesn’t just drop-it crashes. Generic versions, often 80% cheaper, flood the market. But if you’re a patient on a chronic medication, or a hospital running on a tight budget, that shift isn’t automatic. It’s messy. And if you don’t plan for it, you could end up paying more, getting the wrong version, or even going without your medicine.

By 2029, over $90 billion in brand-name drug sales will be up for grabs as patents expire. That’s not a future problem. It’s happening right now. Drugs for diabetes, heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and cancer are losing protection. And while generics are supposed to make care cheaper and more accessible, the reality is more complicated. Many patients don’t know what’s coming. Many systems aren’t ready.

Why your drug might suddenly change-or disappear

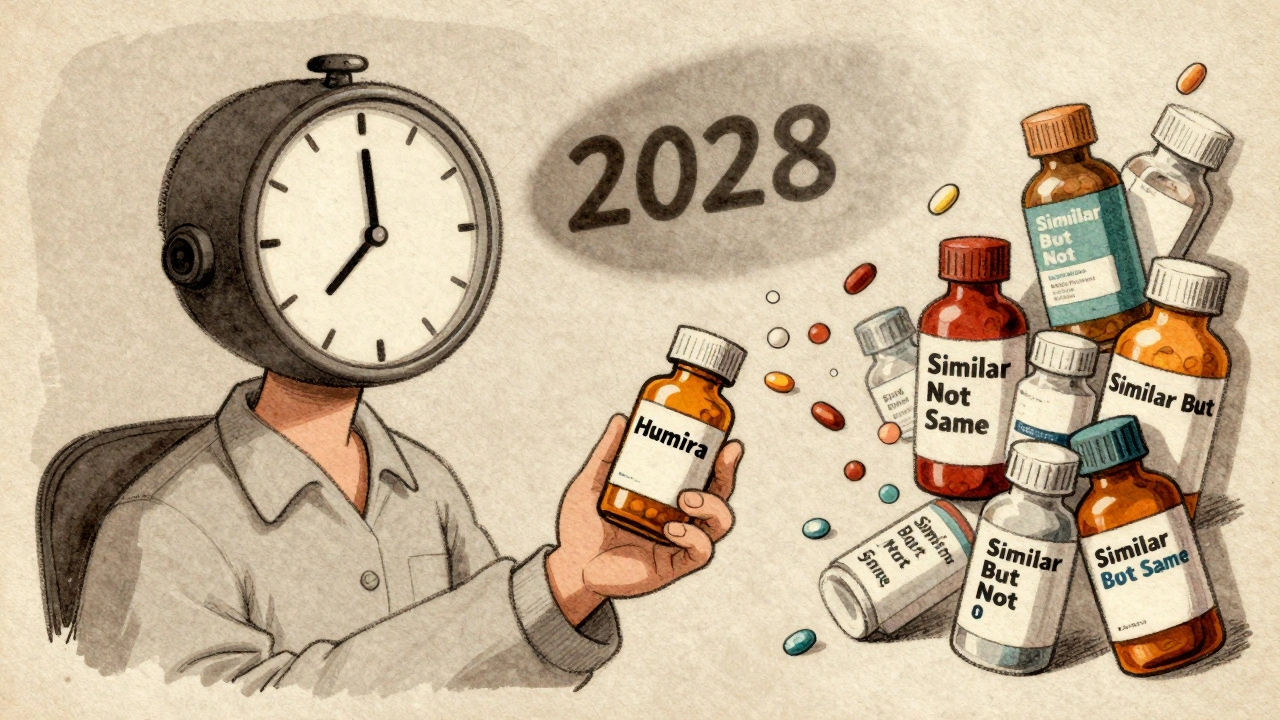

Let’s say you’ve been taking Humira for rheumatoid arthritis for five years. Your doctor prescribed it. Your insurance covered it. Then, one day, your pharmacy says, "We’re switching you to a biosimilar." You’re confused. Is it the same? Will it work? What if you have side effects?

This isn’t rare. By 2028, over 45 biologic drugs will lose patent protection in the U.S. alone. Biologics are complex medicines made from living cells-not simple pills. They’re expensive. And when patents expire, they don’t turn into cheap generics like aspirin. They become biosimilars: similar, but not identical. The FDA says they’re safe. But 37% of patients in a 2022 Kaiser survey reported new side effects after switching, even when the drug met regulatory standards.

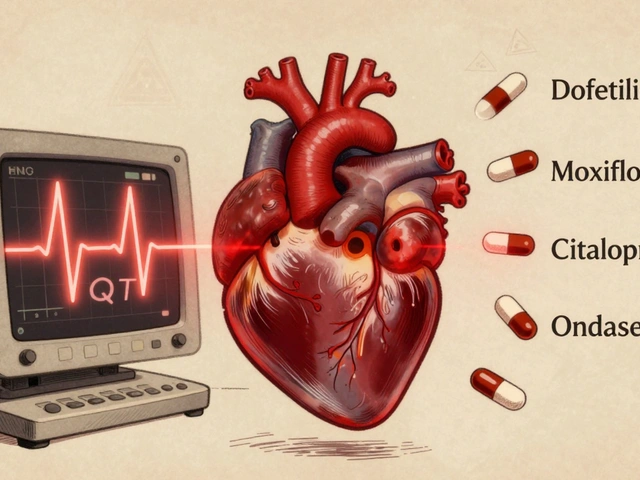

And it’s not just biosimilars. Small-molecule drugs like Lipitor or Plavix face the same fate. Their patents expire, and dozens of generic versions hit the market. But here’s the catch: not all generics are created equal. They must be 80-125% bioequivalent to the brand. That’s a wide range. Some people tolerate one generic just fine. Another gives them nausea or headaches. And if your pharmacy switches you without warning, you might not even know why you feel off.

How drug companies delay the inevitable

You’d think when a patent expires, generics roll in fast. But that’s not always true. Pharmaceutical companies have spent decades building legal and technical walls to keep competition out.

One tactic? Patent thickets. Instead of one patent, they file 20, 30, even 50. Some cover the pill’s shape. Others cover how it’s made, when it’s taken, or even the color of the coating. Nearly 80% of the top 100 selling drugs have dozens of patents stacked on top of the original. This delays generic entry by years.

Then there’s "product hopping." A company stops selling the old version of a drug and pushes patients to a new, slightly modified one-say, an extended-release tablet-then patents that. Suddenly, the generic version of the old drug doesn’t work as a substitute. Patients are forced to switch, often to a more expensive version.

And pay-for-delay deals? Big pharma pays generic makers to wait before launching their cheaper version. In 2023, the FTC reported a 35% drop in these deals thanks to new laws-but they still happen. The result? You pay more for longer.

What healthcare systems must do-starting now

Hospitals, insurers, and pharmacy benefit managers aren’t helpless. But they have to act early. The most successful ones start planning two years before a patent expires.

Here’s what they do:

- Track every patent expiry. In the U.S., over 1,400 drug patents expire each year. Systems that use software like Symphony Health’s PatentSight know exactly what’s coming.

- Build a team. Pharmacy, finance, legal, and clinical staff meet monthly. No silos. Everyone needs to know what’s changing.

- Test the market. Eighteen months out, they check which generics are approved, which are coming, and what prices they’ll charge.

- Update formularies. Twelve months out, they decide which generic or biosimilar to cover. They don’t just pick the cheapest-they pick the one with the best track record for safety and patient tolerance.

- Train doctors and pharmacists. Six months out, they give providers clear guidelines on switching patients. They also prepare patient handouts in plain language.

Systems that do this save an average of $4.7 million per drug. Those who wait until six months out save less than half that.

What patients should do-before the switch

You don’t need to be an expert, but you do need to be prepared.

- Know your drug’s patent status. Go to the FDA’s Orange Book or use a free tool like GoodRx. Search your drug name + "patent expiry." If it’s within 18 months, start paying attention.

- Ask your doctor: "Will I be switched to a generic or biosimilar?" Don’t wait for the pharmacy to tell you. Have the conversation now.

- Ask about alternatives. If your drug is going generic, are there other options that work just as well? Sometimes, a different drug in the same class might be cheaper long-term.

- Track how you feel after a switch. If you start feeling worse-more fatigue, headaches, stomach issues-don’t assume it’s "just you." Call your doctor. It might be the new formulation.

- Check your copay. Sometimes, the generic looks cheaper on paper, but your insurance puts it in a higher tier. Ask your pharmacist: "Is this the lowest-cost option for me?"

And if you’re on Medicare Part D: you’re not alone. In 2022, 42% of beneficiaries had their medication changed after a patent expired. Many didn’t understand why. Ask your plan for a written notice before any switch.

The big gap: biosimilars aren’t playing by the same rules

Small-molecule generics? They’re everywhere. Within a year of patent expiry, 90% of prescriptions switch to them.

Biosimilars? Not even close. Only 38% of biologic prescriptions switch in the first two years. Why?

Because they’re harder to make. They’re expensive to produce. Pharmacies don’t stock them. Doctors are nervous. Patients are scared. And insurance companies? They often don’t push them hard enough.

But things are changing. The FDA has approved 78 biosimilars as of 2023. And in oncology, biosimilars are gaining fast-45% market share within a year. The key? Education. When patients and doctors understand that biosimilars aren’t "second-rate," adoption rises.

What’s next? The law is catching up

For years, the system favored drug companies. But that’s shifting.

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act lets Medicare negotiate prices for some drugs after they lose patent protection. Starting in 2026, 10-20 drugs per year will be affected. That could force even more price drops.

The CREATES Act, passed in 2023, makes it harder for companies to block generic makers from getting samples to test their products-a common tactic to delay competition.

And Congress is now debating the Pharmaceutical Patent Reform Act. If it passes, it could cut generic entry delays by 6-9 months. That means faster savings for patients and systems alike.

Bottom line: Plan ahead or pay the price

Patent expiry isn’t a mystery. It’s predictable. We know exactly which drugs are losing protection, and when. The question isn’t whether it’s coming-it’s whether you’re ready.

For patients: Don’t wait for a surprise switch. Ask questions now. Know your options. Track how you feel after any change.

For systems: Don’t wait until the last minute. Start tracking patents today. Build your team. Update your policies. The savings are real-but only if you act early.

The next few years will be the biggest shift in drug pricing since generics first appeared. Those who plan will save money. Those who don’t will pay more-for their health, their time, and their peace of mind.

What happens to the price of a drug after its patent expires?

After a patent expires, generic or biosimilar versions enter the market. For small-molecule drugs, prices typically drop 80-85% within one year. Biosimilars see slower price declines, often 20-40% in the first year, because they’re harder and more expensive to produce. The exact price depends on how many competitors enter and how aggressively insurers negotiate.

Are generic drugs as safe and effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes-by FDA standards. Generics must prove they’re bioequivalent: they deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. But they can have different inactive ingredients-fillers, dyes, coatings-which sometimes cause side effects in sensitive patients. About 37% of patients report new reactions after switching, even when the drug meets regulatory requirements.

Why do some patients get switched to a different generic every time they refill?

Pharmacies often choose the cheapest generic available at the time of refill. If multiple generics are on the market, the pharmacy may switch between them to get the best price from their supplier. This can cause confusion or side effects if you’re sensitive to different fillers or formulations. Ask your pharmacist to stick with one version if it works for you.

Can I refuse to switch to a generic or biosimilar?

Yes, but it may cost you more. If your doctor writes "Do Not Substitute" on the prescription, the pharmacy must fill it with the brand-name drug. But your insurance may not cover it, or you may have to pay the full difference out-of-pocket. Talk to your doctor about whether switching is safe for you before refusing.

How can I find out when my drug’s patent expires?

Use the FDA’s Orange Book database (search by drug name) or free tools like GoodRx or Drugs.com. Enter your drug’s name and look for "patent expiration" or "LOE" (loss of exclusivity) dates. Many health systems also send alerts to patients whose drugs are nearing expiry. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or doctor.

Do biosimilars work as well as the original biologic drugs?

Yes. Biosimilars are approved by the FDA after rigorous testing to show they’re highly similar to the original biologic, with no clinically meaningful differences in safety or effectiveness. In oncology, biosimilars have matched the original drugs in survival and response rates. But because biologics are complex, some patients or doctors remain cautious. Real-world data shows most patients do well after switching.

Why does it take so long for biosimilars to become widely used?

Biosimilars are expensive to develop and manufacture. They require specialized facilities and testing. Drugmakers also use tactics like exclusive contracts with insurers or rebates to keep doctors prescribing the brand. Many physicians aren’t trained on biosimilars and may be hesitant to switch. Patient education and better reimbursement policies are needed to speed adoption.

Will my insurance cover a biosimilar?

Most insurers cover biosimilars and often encourage or require them because they’re cheaper. But coverage varies. Some plans put biosimilars in the same tier as the brand, while others make you pay more to choose the brand. Check your plan’s formulary or call your insurer before switching.

How can healthcare systems avoid drug shortages when generics launch?

Shortages happen because manufacturers ramp up production too slowly or face supply chain delays. Systems can avoid this by working with multiple generic suppliers, building buffer stock for high-demand drugs, and monitoring FDA shortage lists. Starting planning 18-24 months before expiry gives time to secure reliable sources.

What’s the biggest mistake patients and systems make with patent expiry?

Waiting until the last minute. Patients assume their drug will stay the same. Systems assume generics will automatically lower costs. Both are wrong. Without planning, patients get switched unexpectedly, and systems miss savings. The best outcomes come from starting early-two years before expiry-and staying engaged throughout the transition.

10 Comments

Paul Dixon

December 11, 2025 at 08:59

I was on Humira for years and when they switched me to a biosimilar, I thought I was gonna die. Turns out? I felt better. No more bloating, less fatigue. Turns out my body just hated the brand's filler. Who knew?

Big pharma wants you scared. Don't be. Talk to your doc. Ask for the biosimilar. Save your cash.

Jim Irish

December 11, 2025 at 10:52

Patent expiry is inevitable. The system must adapt. Patients need transparency. Providers need tools. Systems need foresight. Delaying action increases cost and risk. Planning two years ahead is not optional. It is basic fiscal responsibility.

Mia Kingsley

December 12, 2025 at 03:01

OMG so like i read this and i was like wait are we seriously letting big pharma get away with this?? i mean like the color of the pill?? who cares?? and then i found out my insurance switched me to a generic that made me throw up for a week and i was like nope nope nope

also why do all these articles sound like they were written by a robot who only reads press releases??

Aidan Stacey

December 13, 2025 at 04:55

Let me tell you something. I work in a community clinic. We had a patient on Enbrel for 7 years. Switched to a biosimilar. She cried. Said she felt like her body betrayed her. We sat with her. Gave her the data. Showed her the studies. Six weeks later? She thanked us. Said she could finally afford to take her kid to the zoo.

This isn't about drugs. It's about dignity. And we have to fight for it. Together.

matthew dendle

December 15, 2025 at 00:22

so like the whole patent thicket thing is just big pharma being greedy af and the fda lets them get away with it because they got lobbyists on speed dial

and dont even get me started on how pharmacies switch generics like its a game of musical chairs

my grandma took one generic and her knees started swelling like a balloon

they dont care as long as the profit margin stays fat

Monica Evan

December 16, 2025 at 08:22

I used to be a pharmacy tech. Saw it all. One day you're filling 20 scripts for Lipitor. Next week? 18 of them are for atorvastatin. But here's the kicker-some folks get the Walmart generic. Some get the CVS one. Some get the one with the weird chalky taste. Same drug. Different fillers. Different side effects.

Patients deserve consistency. Ask for the same maker every time. Pharmacies will honor it if you push back. And yes, it's worth the 2 extra minutes on the phone.

Courtney Blake

December 18, 2025 at 04:42

This is why America is broken. We let corporations own our health. You think this is about science? No. It's about profit. Every single time. And now you want patients to 'plan ahead'? Like we have time to study patent law while we're trying not to pass out from low blood sugar?

Fix the system. Not the patient.

Lisa Stringfellow

December 19, 2025 at 16:59

I'm just gonna say it. Most of these 'savings' are just shifting costs. Insurance companies don't care if you get a new rash from a generic. They just want the copay lower. And doctors? They're too busy to explain the difference between a biosimilar and a generic. So you get stuck with whatever's cheapest.

And now you're telling us to 'track our symptoms'? Like we have the energy to keep a journal on top of working two jobs and raising kids?

This isn't empowerment. It's neglect dressed up as advice.

Kristi Pope

December 21, 2025 at 04:19

I just want to say thank you to whoever wrote this. I'm a nurse and I've seen too many patients panic when their meds change. This guide? It’s the one I print out and hand to them. Simple. Clear. No jargon. Just facts.

And to everyone saying 'this is too much work'-you're right. It shouldn't be. But until the system fixes itself, we have to be our own advocates. And you're not alone. We're all in this together.

Aman deep

December 21, 2025 at 05:10

In India we have generics everywhere and they work fine. But here in US, the fear around biosimilars is real. My cousin got switched to a Humira biosimilar and was scared to take it. I showed her the WHO and FDA data. She cried. Said she didn't know she had a right to ask. Now she's saving $1200 a month. And she's alive. That's what matters.