Rationing Medications: How Ethical Decisions Are Made During Drug Shortages

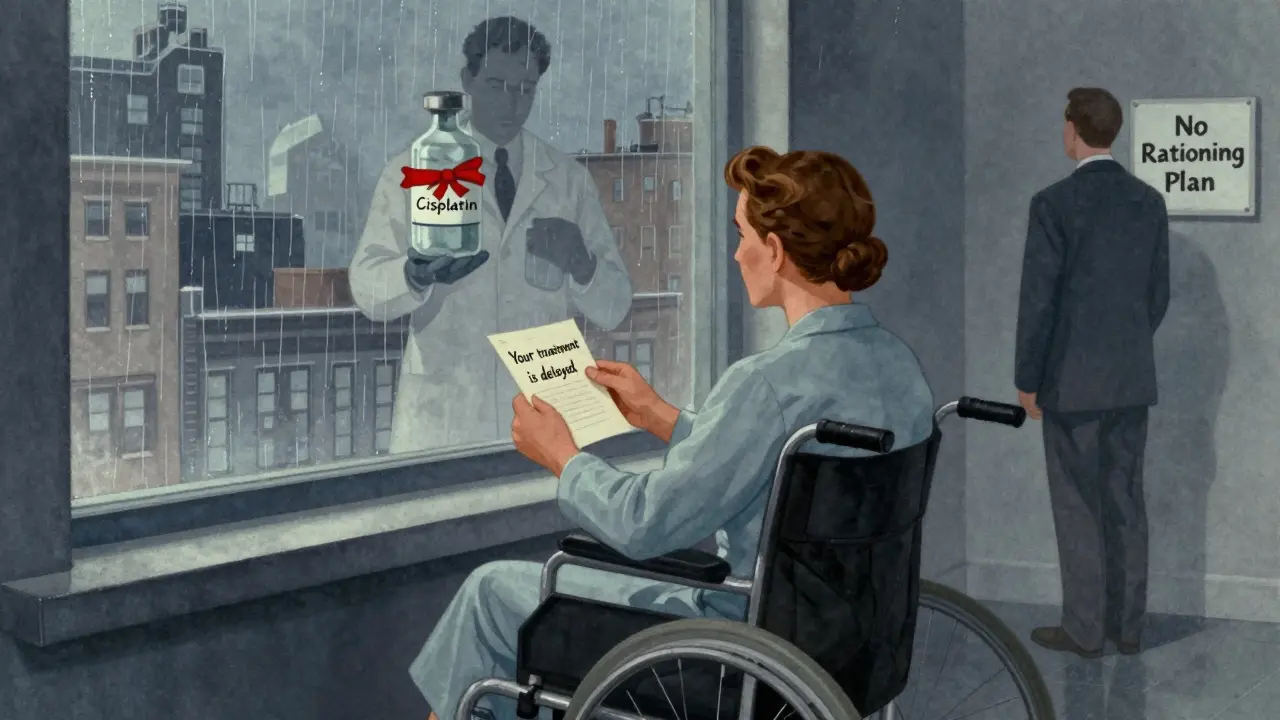

When a life-saving drug runs out, who gets it? This isn’t science fiction. In 2023, carboplatin and cisplatin - two essential chemotherapy drugs - were in such short supply that 70% of U.S. cancer centers had to make impossible choices. One patient gets the dose today. Another waits. Maybe forever. No one wants to be the person deciding this. But someone has to.

Why We’re Talking About Rationing Now

Drug shortages aren’t new, but they’ve gotten worse. In 2005, there were 61 reported shortages in the U.S. By 2023, that number jumped to 319. Most of these are injectable drugs - the kind you get in hospitals, often for cancer, infections, or heart conditions. The problem? A handful of manufacturers make most of these generics. Three companies control 80% of the market. If one factory has a quality issue, or a supply chain hiccup, the whole country feels it. The FDA says 43% of shortages are sterile injectables. That means drugs you can’t just pick up at the pharmacy. These aren’t over-the-counter painkillers. These are treatments that keep people alive. And when they’re gone, hospitals don’t have time to wait.What Rationing Actually Looks Like

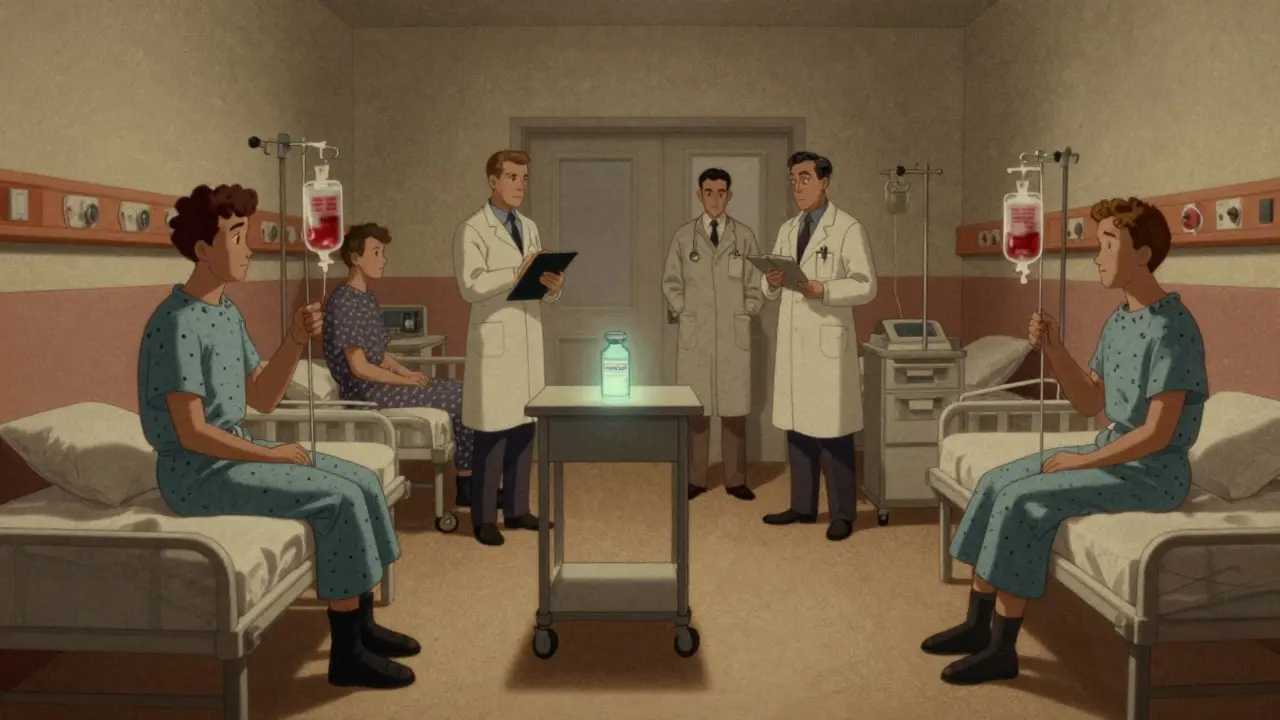

Rationing doesn’t mean giving someone a smaller pill. It means deciding who gets the full dose, who gets a reduced one, and who gets nothing at all. It happens in real time, in exam rooms, in oncology units, in emergency departments. Some hospitals let doctors decide on the spot. A nurse might say, “I’ll give it to the younger patient - they have more years ahead.” Another might pick the one with the best chance of survival. But that’s not fair. It’s not consistent. And it’s not ethical. The real problem? When decisions are made at the bedside, they’re emotional, rushed, and often hidden. A 2022 study found that 51.8% of rationing decisions were made by individual clinicians - without any committee, without any guidelines. And here’s the kicker: only 36% of patients were even told they were being rationed.The Ethical Frameworks That Try to Fix This

There are better ways. Experts have spent years building ethical frameworks to guide these decisions. One of the most respected is the Daniels and Sabin accountability model. It says four things must happen:- Publicity: Everyone - patients, staff, families - must know how decisions are made.

- Relevance: Criteria must be based on evidence, not gut feeling. Who benefits most? Who has the greatest need?

- Appeals: If someone disagrees, there’s a way to challenge the decision.

- Enforcement: Someone has to make sure the rules are followed.

- Is this treatment curative? Or just palliative?

- Is there a viable alternative?

- What’s the expected survival benefit?

- How many years of life could this drug save?

- Tier 1: Curative intent, no alternative - gets the drug.

- Tier 2: Palliative care, but no other option - gets a reduced dose.

- Tier 3: Alternative therapy exists - doesn’t get it.

Why Most Hospitals Still Get It Wrong

You’d think hospitals would follow these guidelines. But they don’t. A 2018 survey of 719 hospitals found only 36% had a standing committee for drug shortages. Of those, just 13.3% included physicians. Only 2.8% had an ethicist on the team. That’s not a committee. That’s a suggestion. Rural hospitals are even worse. Sixty-eight percent have no formal rationing plan at all. Meanwhile, academic centers are better prepared - but still inconsistent. And then there’s the resistance. Doctors hate being told what to do. Pharmacists are overwhelmed. Administrators don’t want to deal with the paperwork. So they wait. They hope the shortage ends. They make decisions quietly. The result? Clinician burnout spikes. A 2022 study found that when rationing is done without structure, burnout rates go up by 27%. Moral distress - that feeling of being forced to do something you know is wrong - becomes common.

What Happens When You Don’t Have a Plan

Without a system, you get chaos. Some departments hoard drugs. Oncology gets the last vial. ICU takes the rest. A patient in the ER dies because the drug was saved for someone else - and no one told them why. Disparities grow. Wealthier patients get priority. Those with better insurance get access. Minority populations? They’re often left out. A 2021 report found 78% of rationing protocols don’t even track equity. They don’t ask: Who’s being left behind? And patients? They’re kept in the dark. Only 36% are told they’re being rationed. That’s not just unethical - it’s a betrayal of trust. One oncologist, Dr. Sarah Chen, told the ASCO forum: “I’ve had to choose between two stage IV ovarian cancer patients for limited carboplatin doses three times this month - with no institutional guidance.” That’s not medicine. That’s survival.What’s Being Done to Fix It

There’s hope. In 2023, ASCO launched a new online decision tool to help hospitals apply ethical criteria in real time. The CDC updated its Crisis Standards of Care toolkit. And in January 2024, pilot programs began in 15 states to certify hospital rationing committees - training them in ethics, communication, and fairness. The FDA is also working on an AI-powered early warning system. It’s supposed to predict shortages before they happen - giving hospitals time to prepare. But the real change needs to come from inside hospitals. Not from federal reports. Not from ethics papers. From action.What Hospitals Can Do Today

You don’t need a perfect system. You just need a system. Here’s what works:- Build a committee. Pharmacy, nursing, medicine, social work, ethics, and a patient rep. No exceptions.

- Train your staff. Eight hours of ethics. Four hours of crisis communication. Make it mandatory.

- Use clear criteria. Don’t say “best chance.” Say “curative intent with no alternative.”

- Document everything. Why was this patient chosen? Was the family told? Record it.

- Communicate with patients. Even if the news is bad, they deserve to know.

What Patients and Families Should Know

If you or someone you love is in treatment, ask:- Is there a shortage of this drug?

- How are decisions being made about who gets it?

- Is there a committee reviewing this?

- Can I see the criteria being used?

- Was I told about this? If not, why not?

It’s Not About Saving the Most Lives - It’s About Fairness

Ethical rationing isn’t about picking the “most deserving.” It’s about treating everyone with dignity, even when there’s not enough to go around. It’s about saying: We won’t let chaos decide who lives or dies. We will make hard choices - together. And we will be honest about them. The drugs are running out. But the ethics don’t have to.Is medication rationing legal in the U.S.?

Yes, but only under specific conditions. Rationing isn’t illegal - it’s a last resort during public health emergencies when supply can’t meet demand. What’s illegal is making those decisions arbitrarily, without transparency, or based on discrimination. Federal guidelines from the FDA, ASHP, and ASCO require structured, ethical frameworks. Hospitals that don’t follow them risk legal and ethical liability.

Why aren’t more hospitals using ethical rationing committees?

It’s expensive, time-consuming, and uncomfortable. Building a committee takes staff, training, and leadership buy-in. Many hospitals are understaffed. Others fear the backlash - telling patients they won’t get treatment is hard. And without federal mandates, there’s no penalty for not doing it. So most just wing it - even though studies show committee-based systems reduce clinician distress and improve fairness.

Can patients appeal a rationing decision?

They should be able to - but most hospitals don’t have a formal process. Ethical frameworks like Daniels and Sabin require an appeals mechanism. In practice, only a handful of academic centers have one. Patients often don’t even know they’re being rationed, let alone how to challenge it. This is a major gap in current systems. Advocacy groups are pushing for standardized appeal rights as part of national guidelines.

Are generic drugs the main cause of shortages?

Yes. Over 80% of drug shortages involve generic injectables - especially sterile ones like chemotherapy, antibiotics, and anesthetics. These drugs have low profit margins, so manufacturers cut corners. Many are made overseas, and supply chains are fragile. When one factory fails, there’s no backup. The market is dominated by just three companies, making the system vulnerable to single points of failure.

Is there a shortage of cancer drugs right now?

As of early 2026, several key cancer drugs remain in short supply, including carboplatin, cisplatin, doxorubicin, and vincristine. The FDA’s Drug Shortage Database shows ongoing issues with sterile injectables used in oncology. While some shortages have eased since 2023, many hospitals still operate under rationing protocols. The American Society of Clinical Oncology continues to update its guidance as new data comes in.

How can I find out if my medication is in short supply?

Check the FDA’s Drug Shortage Database, which is updated weekly. Your pharmacy or oncology clinic should also be able to tell you if a drug is in short supply. If you’re concerned, ask: “Is there a known shortage for this medication? Are there alternatives? How are decisions being made about who gets it?” Don’t wait - ask early.

8 Comments

Katherine Carlock

January 13, 2026 at 00:31

I’ve had a family member go through chemo during a shortage, and honestly? The silence was worse than the shortage itself. No one told us why the drug was delayed. We just got told ‘it’s complicated.’ That’s not care, that’s avoidance. Hospitals need to stop hiding behind ‘we’re doing our best’ and start being transparent. People deserve to know what’s happening to their bodies.

Sona Chandra

January 14, 2026 at 21:47

OMG this is insane 😭 How is this even legal?? Doctors playing god with people’s lives?? And they wonder why patients lose trust?? I’d riot if my mom got told ‘you’re tier 3’ because some suit decided she ‘has alternatives’ - when the alternative is a $20k/month drug no insurance covers. This isn’t medicine, it’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

beth cordell

January 16, 2026 at 07:43

Just read this and cried in my coffee ☕️💔 I work in hospice and we’ve had to stretch morphine doses because of supply issues. No one talks about how this breaks the nurses. We’re not heroes-we’re just trying not to cry in the supply closet. Someone please fix this. 🙏

Lauren Warner

January 17, 2026 at 10:46

Let’s be real-the ‘ethics committees’ are performative. You think a 12-person committee with a social worker and a ‘patient rep’ who’s a hospital volunteer actually makes a difference? No. They rubber-stamp what the pharmacy director says. And the ‘criteria’? They’re vague enough to let bias slide in. You want fairness? Ban the word ‘potential’ from clinical decision-making. Use hard data. Or stop pretending you care.

Lelia Battle

January 18, 2026 at 05:08

The deeper issue here isn’t scarcity-it’s the erosion of moral infrastructure in healthcare. We’ve outsourced ethical responsibility to algorithms and ad hoc decisions because confronting systemic failure is inconvenient. The Daniels and Sabin model isn’t a checklist-it’s a covenant. A promise that when resources are finite, dignity remains infinite. Yet we treat it like a policy memo. We mistake structure for morality. That’s the real tragedy.

Rinky Tandon

January 20, 2026 at 04:49

Let me break this down with clinical precision: the systemic failure stems from the commodification of sterile injectables under neoliberal pharmaceutical economics. The oligopolistic market structure, dominated by three vertically integrated manufacturers with negligible regulatory oversight, creates a classic tragedy of the commons scenario. Add to that the absence of mandatory ethical governance frameworks and the pathological avoidance of distributive justice discourse in clinical settings-and you have institutionalized moral hazard. We are not managing shortages-we are enabling structural violence disguised as triage.

Ben Kono

January 20, 2026 at 22:39

why do they even make these drugs in one country why not have 5 factories spread out so if one goes down its not the whole country

Cassie Widders

January 21, 2026 at 00:04

My dad’s oncologist just told him they were switching him to a different drug because carboplatin was ‘unavailable.’ No explanation. No alternatives discussed. Just… ‘we’ll figure it out.’ I didn’t know until I read this post. That’s the real failure-not the shortage. It’s the silence.