Theophylline Levels: Why NTI Monitoring Is Critical for Safe and Effective Treatment

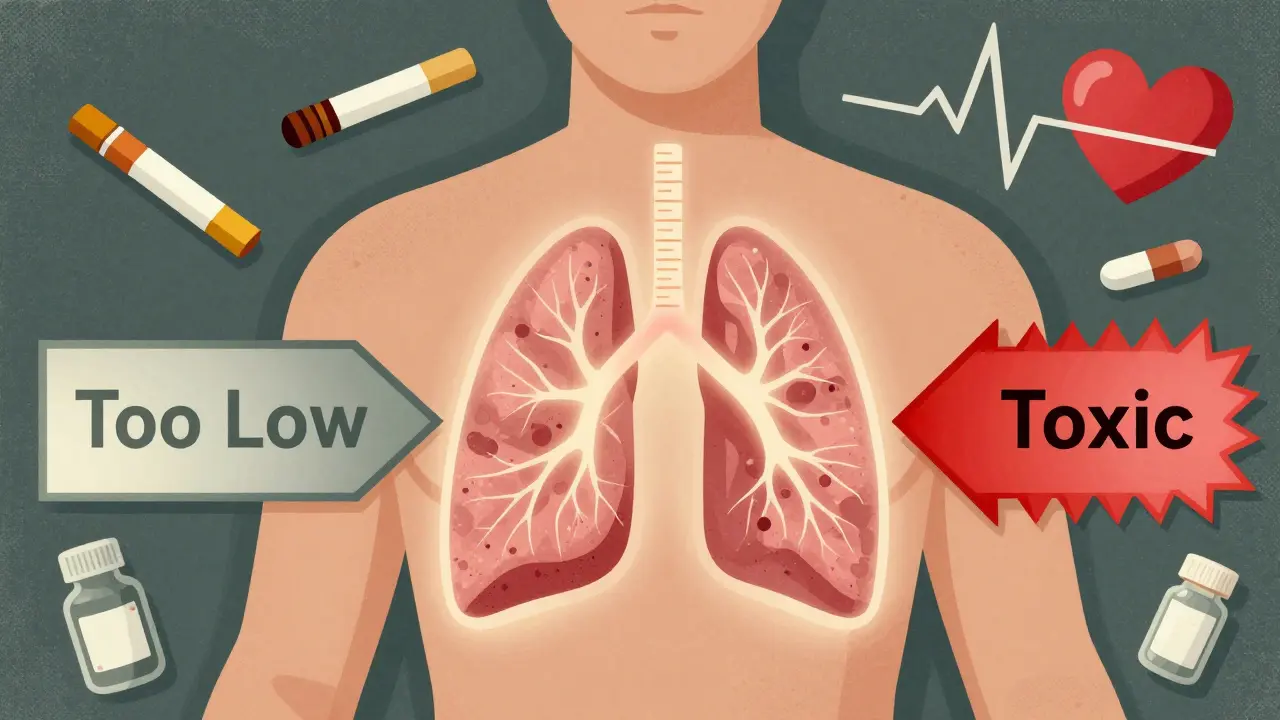

When a drug works in a narrow window-too little and it does nothing, too much and it kills-you can't afford to guess. That's the reality with theophylline is a bronchodilator used for asthma and COPD with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) that demands precise blood level monitoring. Also known as theophylline, it was first introduced in the 1930s and still saves lives today, but only when carefully managed.

Most asthma patients today use inhalers-inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta-agonists. But for some, those aren’t enough. When symptoms persist despite high-dose inhalers, doctors turn to theophylline. It’s not glamorous. It’s old. It’s cheap. A month’s supply costs $15 to $30, compared to $200-$400 for biologic drugs. But its value isn’t in cost alone. Theophylline reduces inflammation in the airways by restoring HDAC2 function, a mechanism that newer drugs often miss. But here’s the catch: the difference between healing and harming is razor-thin.

The Magic Number: 10-20 mg/L

The therapeutic range for theophylline is 10 to 20 mg/L (or 10-20 μg/mL). Below 10, and you’re not getting bronchodilation. Above 20, and you’re flirting with disaster. Seizures, irregular heartbeats, vomiting, tremors-these aren’t rare side effects. They’re predictable outcomes of unmonitored dosing. Some patients respond well at 5-15 mg/L, but that’s the exception, not the rule. And even within that range, toxicity can creep in silently. One patient might tolerate 18 mg/L for years. Another hits 15 and ends up in the ER.

Why Your Dose Doesn’t Tell the Whole Story

Doctors don’t just eyeball the dose. They can’t. Theophylline doesn’t follow simple rules. Its metabolism is messy. It’s processed by the liver-specifically the CYP1A2 enzyme-and that enzyme is easily thrown off by everyday things. Smoking? It boosts clearance by 50-70%. That means a smoker might need double the dose of a non-smoker just to hit the same blood level. Quit smoking overnight? Levels can spike dangerously within days.

Age matters. After 60, liver function slows. Clearance drops. A dose that was safe at 50 becomes toxic at 70. Liver disease? Clearance can drop by 50% or more. Heart failure? Same thing. Pregnancy? In the third trimester, clearance falls by 30-50%. That’s why pregnant women on theophylline need monthly checks.

And then there are the drugs. Macrolide antibiotics like erythromycin and clarithromycin can increase theophylline levels by 50-100%. Cimetidine, a common heartburn drug, does the same. Allopurinol, used for gout, is another culprit. On the flip side, carbamazepine (for seizures), rifampicin (for TB), and even St. John’s Wort can slash levels by 30-60%. A patient stable for months can suddenly lose control because they started a new medication-and no one checked their theophylline level.

When and How to Monitor

You can’t just test once and forget. Steady state takes time. After starting theophylline or changing the dose, you need to wait five days for immediate-release tablets, or three days for extended-release forms, before drawing blood. And timing matters. For immediate-release, draw right before the next dose-this is the trough, the lowest level. For extended-release, wait 4-6 hours after the dose. Test at the wrong time, and you’ll misread the whole picture.

Stable patients? Check every 6-12 months. High-risk? Monthly. That includes:

- Patients over 60

- Those with heart failure or liver disease

- Pregnant women

- Anyone starting or stopping antibiotics, antifungals, or seizure meds

- Patients who’ve changed smoking habits or alcohol intake

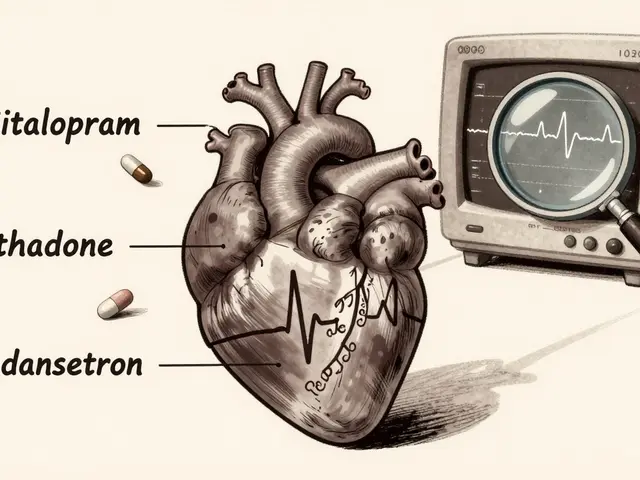

And don’t forget: if a patient starts vomiting, shaking, or feels their heart racing, test immediately. These aren’t just side effects-they’re warning signs of toxicity. One 2023 case report showed a 68-year-old man with COPD develop ventricular tachycardia after starting ciprofloxacin. His theophylline level jumped from 14 mg/L to 28 mg/L in 72 hours. He survived. Many don’t.

Beyond the Blood Level

Checking theophylline alone isn’t enough. You need to look at the whole picture. Tachycardia? Heart rate over 100 bpm? That’s a red flag. Insomnia, anxiety, tremors? That’s CNS toxicity. Low potassium? Common. Theophylline doesn’t directly lower potassium, but it’s often used with other drugs that do-like beta-2 agonists and diuretics. Low potassium makes arrhythmias more likely. Check electrolytes. Check blood gases. Check the full blood count. Bone marrow suppression is rare now, but it still happens.

And if the patient is getting IV theophylline? Never mix it with dextrose. It can cause hemolysis or pseudo-agglutination. That’s not a rumor-it’s in the manufacturer’s guidelines. Use saline. Always.

The Cost of Not Monitoring

One study in a community hospital showed that after implementing a strict monitoring protocol, adverse drug events dropped by 78%. Asthma control improved by 35%. That’s not magic. That’s basic pharmacology.

On the flip side, the U.S. poison control centers report a 23% year-over-year rise in theophylline toxicity cases between 2020 and 2023. Most involve elderly patients with undiagnosed liver or kidney problems. Clinicians miss it because they assume the dose is fine. But dose doesn’t equal level. Level equals safety.

Approximately 15% of adverse events happen because the dose wasn’t adjusted for liver disease. 22% happen because of unmonitored drug interactions. And here’s the kicker: a 2024 study suggested low-dose theophylline (200 mg/day) might be safe without monitoring. But the European Respiratory Society, the American Thoracic Society, and the American College of Chest Physicians all say: no. Even low doses carry risk. Pharmacokinetics don’t care about your dose. They care about your liver, your kidneys, your age, your other meds, your smoking habit. And they change daily.

What’s Next?

Point-of-care testing is coming. Three companies-TheraTest Diagnostics, PharmChek Solutions, and RapidTherapeutics-are testing handheld devices that could give results in under five minutes. Imagine a clinic visit where you get your level checked before you leave. No waiting days for a lab report. No missed doses. No surprises.

But until then? The standard of care hasn’t changed. Blood draws. Timing. Context. Awareness. If you’re prescribing theophylline, you’re responsible for its levels. Not the patient. Not the pharmacist. You. That means knowing when to test. Knowing what to look for. Knowing what drugs interact. Knowing how age and lifestyle change the game.

Theophylline isn’t going away. It’s too cheap, too effective for some, and too valuable in low-resource settings. But it’s also too dangerous to ignore. Monitoring isn’t a burden-it’s the difference between breathing easy and ending up on a ventilator.

What is the therapeutic range for theophylline?

The therapeutic range for theophylline is 10-20 mg/L (or 10-20 μg/mL). Below 10 mg/L, the drug typically doesn’t provide meaningful bronchodilation. Above 20 mg/L, the risk of serious toxicity-including seizures, arrhythmias, and vomiting-rises sharply. Some patients may respond to levels as low as 5-15 mg/L, but this is not the norm and requires individualized assessment.

Why is theophylline considered a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug?

Theophylline is an NTI drug because the difference between its effective dose and toxic dose is very small. A slight increase in blood concentration-due to changes in metabolism, drug interactions, or organ function-can push a patient from therapeutic benefit into life-threatening toxicity. This is unlike drugs with wide therapeutic windows, where higher doses are generally safer.

How often should theophylline levels be checked?

Initial monitoring should occur 5 days after starting therapy or 3 days after a dose change. For stable patients, levels should be checked every 6-12 months. High-risk patients-including those over 60, with liver or heart failure, pregnant women, or those on interacting drugs-need checks every 1-3 months, or even monthly. Additional testing is required after any change in smoking status, alcohol use, or medication.

What medications interact with theophylline?

Drugs that inhibit CYP1A2 (like erythromycin, clarithromycin, cimetidine, and allopurinol) can increase theophylline levels by 50-100%. Drugs that induce CYP1A2 (like carbamazepine, rifampicin, and St. John’s Wort) can decrease levels by 30-60%. Even common antibiotics and herbal supplements can cause dangerous shifts. Always review all medications when prescribing or continuing theophylline.

Can you monitor theophylline without blood tests?

No. Clinical symptoms alone are unreliable. A patient may feel fine with a level of 28 mg/L-or feel terrible at 12 mg/L. Individual variability is too high. Even low doses (200 mg/day) carry risk due to unpredictable metabolism. Blood level monitoring remains the only reliable method to ensure safety and efficacy. Point-of-care devices are in development, but serum testing is still the standard.

What are the signs of theophylline toxicity?

Early signs include nausea, vomiting, tremors, insomnia, and palpitations. More severe toxicity presents with tachycardia (heart rate >100 bpm), seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, and hypokalemia. Seizures and ventricular tachycardia are medical emergencies. If toxicity is suspected, stop the drug immediately and check serum levels. Supportive care and activated charcoal may be needed.

Why does smoking affect theophylline levels?

Smoking induces the CYP1A2 enzyme in the liver, which speeds up the breakdown of theophylline. Smokers may clear the drug 50-70% faster than non-smokers. This means they often need higher doses to reach therapeutic levels. But if a patient quits smoking, their clearance drops rapidly-sometimes within days-causing levels to spike dangerously. Dose adjustments are mandatory after any change in smoking status.

Is theophylline still used today?

Yes. While newer inhalers and biologics are preferred, theophylline remains a third-line option for severe asthma and COPD that doesn’t respond to standard therapy. It’s especially valuable in resource-limited settings due to its low cost. Approximately 1.2 million U.S. patients and 850,000 in Europe still use it annually. Its anti-inflammatory effects, particularly in severe disease, make it uniquely useful despite the monitoring burden.

If you’re managing a patient on theophylline, don’t assume. Don’t guess. Test. Adjust. Re-test. The narrow window doesn’t forgive mistakes. But with careful monitoring, it can save lives.

10 Comments

Jonah Mann

February 7, 2026 at 06:02

Man i thought i was the only one who still uses theophylline... my doc switched me over from albuterol after 3 yrs of flares. Cost is insane for biologics. But yeah, i got lucky. My levels stayed stable... until i started taking cimetidine for heartburn. Didn't even think about it. Ended up in the ER with tremors and a heart rate of 120. Never again. Always check interactions. Seriously.

Tatiana Barbosa

February 8, 2026 at 21:31

THIS. This is why I love old-school meds. Cheap. Effective. But ONLY if you're paying attention. I’m a pulmonology NP and I’ve seen too many elderly patients crash because someone didn’t adjust for liver decline or a new antibiotic. We need to bring back the old-school monitoring culture. No shortcuts. Blood levels aren’t optional-they’re life insurance.

THANGAVEL PARASAKTHI

February 10, 2026 at 01:14

Interesting read. In India, theophylline is still widely used due to cost. But monitoring? Not so much. Many clinics don’t even have access to labs. We rely on symptoms and experience. It’s risky. But we make it work. Maybe point-of-care devices will change that. Hope so.

MANI V

February 10, 2026 at 06:47

Of course you need monitoring. What did you expect? People take this drug like it’s aspirin. You don’t just pop pills and hope. This isn’t a game. If you can’t handle the science, don’t prescribe it. Stop being lazy. This isn’t 1995 anymore.

Susan Kwan

February 11, 2026 at 18:10

Wow. A whole article about something that should be taught in med school 101. Did we really need a 10-paragraph essay to tell us that NTI drugs need monitoring? Maybe next time, explain how to tie your shoes.

Random Guy

February 12, 2026 at 20:40

So let me get this straight… you’re telling me that smoking makes you need MORE of this drug… and then if you quit… you might DIE? That’s like saying your car’s gas pedal gets stuck when you stop pumping gas. This is wild. Who designed this? Did the devil write the pharmacokinetics?

Ryan Vargas

February 13, 2026 at 17:35

Think deeper. Theophylline isn’t just a drug-it’s a mirror. It reflects our entire medical system’s obsession with reductionism. We reduce a human being to a CYP1A2 enzyme, a serum level, a dosing chart. But what about the soul? The emotional toll of being told you’re a ‘high-risk patient’? The shame of being ‘unstable’? The theophylline level is just the symptom. The disease is our failure to see the person behind the lab result. We’re treating numbers, not lives.

Ken Cooper

February 14, 2026 at 07:45

Wait, so if someone quits smoking, their theophylline level can spike in DAYS? That’s wild. I had a patient who quit cold turkey after 30 years. We didn’t adjust his dose. He ended up with a level of 24. Had to ICU him. I still feel bad. Why isn’t this in every patient handout? Shouldn’t there be a warning label? Like ‘If you quit smoking, call your doctor immediately’?

Tasha Lake

February 14, 2026 at 15:31

As a clinical pharmacist, I’ve seen this too many times. The real issue? Polypharmacy. Elderly patients on 8+ meds. Theophylline gets lost in the shuffle. We need automated alerts in EHRs. If a patient on theophylline gets prescribed clarithromycin? System should scream. Stop. Don’t fill. Notify provider. We have the tech. We just don’t use it. Let’s fix that.

Sam Dickison

February 15, 2026 at 05:36

One sentence: If you’re prescribing theophylline and not checking levels, you’re not a doctor-you’re a roulette wheel.