Why Most Drugs Don't Have Authorized Generics - And What It Means for Your Prescription Costs

Not every drug has an authorized generic - and that’s not an accident. It’s by design.

If you’ve ever picked up a prescription and seen a different-looking pill with the same name, you might have thought it was just another generic. But if it’s an authorized generic, it’s actually the exact same pill made by the brand-name company, just sold under a different label. No changes in ingredients. No changes in manufacturing. Just a lower price tag.

So why don’t all drugs have them? The answer isn’t about science or safety. It’s about money, strategy, and who controls the market.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic (AG) is a brand-name drug sold without the brand name on the label. It’s made by the same company, in the same factory, with the same formula, using the same equipment. The only difference? It’s sold as a generic - at generic prices.

Unlike traditional generics, which must prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand through costly and time-consuming FDA reviews, authorized generics skip all that. They’re produced under the original New Drug Application (NDA) the brand company already has. That means they can hit the market in weeks, not years.

For example, when Mylan launched its authorized generic version of the EpiPen in 2016, it wasn’t waiting for approval. It was just re-labeling the exact same auto-injector it already made for the brand version. The result? A 20% drop in price almost overnight.

Why Only Some Drugs Get Authorized Generics

Only about 1,215 authorized generics existed in the U.S. as of 2019 - out of thousands of prescription drugs. That’s less than 5% of all branded medications. Why so few?

Because AGs aren’t created to help patients. They’re created to protect profits.

Brand manufacturers use authorized generics as a tool - not to increase access, but to control competition. The most common scenario? When a generic company files to challenge a patent, the brand company can launch its own AG right away. That cuts the generic company’s profits before they even start.

The FDA gives the first generic applicant 180 days of exclusivity. During that time, they usually have no competition. But if the brand company launches an AG during those 180 days, suddenly there are two versions of the same drug on the shelf - one from the generic company, one from the brand. And guess who wins? The one with the lower price. Often, that’s the AG.

The Federal Trade Commission found that when an AG enters during exclusivity, the first generic’s revenue drops by 40-52%. That’s a massive hit. So many generic companies now avoid challenging patents at all - especially if they know the brand might launch an AG.

The Price Impact - And Who Really Benefits

Yes, authorized generics can lower prices. But not always - and not for long.

When Teva launched its AG version of Protonix in 2010, it priced it 35% below the brand. That helped patients. But here’s the catch: Teva owned both the brand and the AG. So they were essentially selling the same drug at two price points - and keeping all the profits.

For consumers, the savings during the 180-day exclusivity window are real. The FTC found retail prices dropped 4-8% and wholesale prices fell 7-14% when an AG was present. For a $100 prescription, that’s $4-$14 saved. Not nothing. But after the exclusivity period ends, prices often creep back up - especially if the AG is the only generic left.

And here’s the irony: patients often don’t even know they’re getting an AG. Pharmacists report confusion when a prescription switches from a brand to an AG - the pill looks identical, but the packaging is different. One study found 27% more prescription errors occurred when both versions were available.

Who Decides If an AG Gets Made?

No regulator. No law. Just the brand company.

There’s no requirement for a drug maker to launch an authorized generic. It’s purely a business decision. And it’s almost always tied to revenue.

According to Evaluate Pharma, 89% of drugmakers with annual sales over $1 billion have used AGs. Only 22% of companies with drugs under $100 million in sales have. Why? Because the bigger the drug, the bigger the risk of generic competition - and the bigger the incentive to control it.

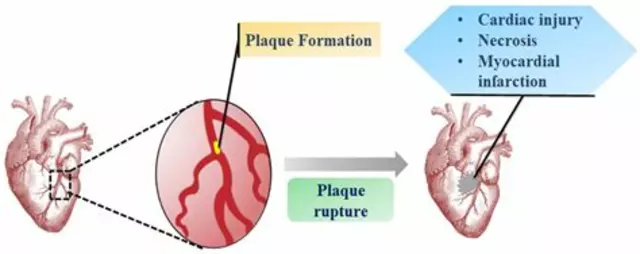

Top-selling AGs are clustered in high-revenue areas: 42% are for brain and nervous system drugs (like antidepressants and ADHD meds), 28% for stomach and gut drugs (like acid reflux pills), and 19% for heart medications. These are the drugs people take for years - and pay for every month.

If a drug makes $500 million a year, the brand company has a strong reason to launch an AG to fend off competitors. If it makes $50 million? Not worth the hassle.

The Hidden Cost: Killing Generic Competition

Authorized generics don’t just compete with generics - they discourage them from ever entering the market.

Generic companies spend millions to challenge patents. They hire lawyers, run clinical studies, and wait years for approval. But if they know the brand company can launch an AG during their 180-day exclusivity window, their chances of making a profit drop dramatically.

One study found that when AGs are a possibility, generic companies need at least a 10% chance of winning a patent lawsuit to justify the cost. Without AGs, that number drops to just 4%. That’s a huge barrier.

Harvard’s Aaron Kesselheim put it plainly: AGs give patients short-term savings but hurt long-term competition. They turn the Hatch-Waxman Act - designed to boost generic access - into a tool for delaying it.

Even the FTC agrees. In 2023, they filed a legal brief arguing that AGs during exclusivity periods are “anti-competitive.” They’re pushing Congress to ban them during that window.

What’s Changing - And What’s Not

The FDA now updates its AG list quarterly instead of annually. That’s better transparency. But it doesn’t change who controls the system.

Legislation like the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics Act has been reintroduced in Congress multiple times. It would ban brand companies from launching AGs during the 180-day exclusivity period. So far, it’s stalled.

Meanwhile, drugmakers are getting smarter. Instead of launching AGs outright, they’re now including “no-AG” clauses in patent settlement deals. In 2022, 78% of these deals included promises not to launch an AG - up from 62% in 2013. That means the threat of an AG is being used as a bargaining chip - not to lower prices, but to buy silence.

And while biosimilars are growing, they’re mostly for injectable drugs - not pills. For the vast majority of medications you take daily, AGs are still the only alternative to brand-name pricing.

What This Means for You

If you’re paying for a brand-name drug, check if an authorized generic exists. Ask your pharmacist. Look up the drug on the FDA’s list. You might save a few dollars.

But don’t assume the system is working for you. The fact that only a small fraction of drugs have AGs - and only when it benefits the brand - tells you everything you need to know.

Generic competition should be about choice, not control. But right now, the people who make the drugs also decide who gets to compete. And that’s not how a free market should work.

Until laws change, the only way to know if your drug has an authorized generic is to ask. And even then, you’re relying on a company’s willingness to let you save money - not their obligation to let you.

Are authorized generics the same as regular generics?

Yes and no. Authorized generics are physically identical to the brand-name drug - same ingredients, same factory, same packaging (just without the brand logo). Regular generics are made by other companies and must prove they work the same way through FDA testing. Authorized generics skip that step because they’re made under the brand’s original approval.

Why don’t all brand-name drugs have authorized generics?

Because brand manufacturers only launch them when it helps their business. If a drug makes over $500 million a year and faces patent challenges, they’re more likely to use an AG to block competitors. Smaller drugs rarely get them because the cost of launching an AG isn’t worth the risk.

Do authorized generics lower prices permanently?

Usually not. Prices drop during the 180-day exclusivity window when the AG first launches - sometimes by 10-35%. But after that, if no other generics enter, prices often rise again. The AG becomes the only low-cost option, and the brand company still controls supply.

Can I ask my pharmacist for an authorized generic?

Yes. Ask if there’s an authorized generic version of your brand-name drug. Pharmacists can check the FDA’s list or their pharmacy system. Some AGs are listed under the brand name with a note like “AG” or “authorized generic.” You might need to request it specifically - it won’t always be substituted automatically.

Are authorized generics safe?

Yes. Since they’re made by the same company using the same process as the brand-name drug, they’re just as safe and effective. The FDA considers them identical in quality. The only difference is the label and the price.

Why is there so much confusion around authorized generics?

Because they look exactly like the brand-name drug - just with different packaging. Patients and even pharmacists sometimes think they’re switching between different generics, when they’re actually switching between the brand and its own generic version. This leads to errors in dispensing and confusion about why the pill changed color or shape.

Is there a list of all authorized generics?

Yes. The FDA maintains a public list of authorized generics on its website. It includes the brand name, the AG version, and the manufacturer. The list is updated quarterly now, but it’s not always easy to navigate. You can search by drug name or manufacturer.

Do authorized generics affect insurance coverage?

Usually not. Most insurance plans treat authorized generics the same as regular generics - they’re placed in the same tier and have the same copay. But some plans may not recognize them as generics unless you ask. Always check your plan’s formulary or call your insurer to confirm.

13 Comments

david jackson

December 26, 2025 at 20:56

Okay, so let me get this straight - the same pill, same factory, same everything, but suddenly it’s cheaper? And the company that makes it decides whether or not to let you have it? That’s not capitalism, that’s a rigged game of musical chairs where the chairs are life-saving medication and the music is corporate profit margins. I’ve been on a $400/month antidepressant for years - finally found out there was an authorized generic for $80. I didn’t even know it existed until a pharmacist offhandedly mentioned it. Why isn’t this information pushed to patients? Why is it buried under layers of legal jargon and pharmaceutical secrecy? This isn’t innovation. It’s exploitation dressed up as a discount.

Jody Kennedy

December 28, 2025 at 06:38

Y’all need to start asking for AGs at the pharmacy. Seriously. I didn’t know about them until last year, and now I save like $120 a month on my blood pressure med. It’s literally the same pill - just no fancy logo. Ask for it by name. Don’t let them just give you the brand. You’re not being annoying - you’re being smart. And if they give you side-eye? Tell ‘em the FTC says they’re anti-competitive. 😎

christian ebongue

December 29, 2025 at 00:30

AGs = brand companies playing 4d chess with generic makers. Also, 89% of big pharma firms use em. No surprise. The system’s broken. But hey, at least your EpiPen isn’t $600 anymore. 😅

Alex Ragen

December 29, 2025 at 02:48

Oh, so the very entities that spent billions lobbying against generic competition now get to decide - with zero oversight - whether you get a cheaper version of their own drug? How poetic. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to democratize access. Now it’s a tool for monopolistic theater. The FDA updates its list quarterly? Cute. Like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic while the pharma CEOs sip champagne in the first-class lounge. We don’t need transparency - we need a ban. And maybe a public execution of a few CMOs. Just a thought.

Lori Anne Franklin

December 31, 2025 at 01:12

i had no idea ags even existed until my pharmacist mentioned it last month. i was so mad i didn’t know sooner. but now i’m like… why isn’t this common knowledge? like, shouldn’t this be on every drug box? or at least in the ads? i feel like we’re all being kept in the dark on purpose. but hey, at least now i’m asking. 🙌

wendy parrales fong

January 1, 2026 at 06:36

It’s wild to think that the same person who made your medicine in the same lab with the same tools can just decide whether you get to pay less for it. It’s like buying a car and finding out the manufacturer made an identical version for half the price - but only gave it to some people because they felt like it. We need to stop treating healthcare like a luxury game and start treating it like a human right. No one should have to dig through FDA lists just to afford their pills.

Jeanette Jeffrey

January 1, 2026 at 07:05

Oh wow, so the pharma giants are using AGs to bully smaller generic companies out of the market? Shocking. I mean, who would’ve thought that a multi-billion-dollar industry with zero accountability would use every loophole to maximize profits? Next they’ll be selling air in branded bottles and calling it ‘premium oxygen.’ This isn’t capitalism - it’s feudalism with better marketing. And you? You’re just the serf paying for the privilege of breathing.

Kuldipsinh Rathod

January 2, 2026 at 11:19

I’m from India, and here generics are everywhere - cheap, accessible, and trusted. But reading this made me realize how messed up the U.S. system is. You have the tech, the science, the resources - but you let profit decide who gets life-saving meds? That’s not a healthcare system. That’s a casino. I hope more people find out about AGs. You deserve better.

carissa projo

January 3, 2026 at 10:55

Imagine if your doctor handed you a pill and said, ‘This is the exact same as the expensive one, but we’re giving you the cheaper version because we care about you.’ Now imagine that same doctor then quietly tells you, ‘But only if the company feels like it.’ That’s the reality. We’re not just fighting for lower prices - we’re fighting for dignity. You shouldn’t have to beg, research, or beg your pharmacist to get what you’re already paying for. You’re not a customer. You’re a human being. And your health isn’t a spreadsheet.

Zina Constantin

January 4, 2026 at 06:43

Authorized generics are not a public health win - they are a corporate maneuver disguised as consumer relief. The FDA’s quarterly updates are a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. The fact that 78% of patent settlements now include no-AG clauses proves this is systemic, not accidental. We need legislation, not awareness campaigns. And we need to stop celebrating minor savings as victories when the root cause remains untouched. This isn’t progress. It’s performance.

Dan Alatepe

January 5, 2026 at 20:31

bruh… i just found out my anxiety med has an ag. i’ve been paying $150/month for 3 years. same pill. same factory. $45 now. i’m crying. not happy tears. angry tears. how many people are still paying full price because they don’t know? this system is built to make us feel lucky when we get a discount. we should be furious we had to fight just to get what’s ours. 🫂

Michael Bond

January 6, 2026 at 13:57

AGs are a band-aid. The real fix? Ban them during exclusivity. End the patent games. Let real competition happen.

Matthew Ingersoll

January 8, 2026 at 06:05

There’s a reason this isn’t common knowledge. If people knew how easily they could save hundreds a month, the whole system would collapse. The drugmakers know it. That’s why they keep it quiet. You’re not supposed to ask. You’re supposed to just pay. But now you know. And that changes everything.